MS Family Planning 201: Breastfeeding, DMTs, and the Risk of Postpartum Relapse

The risk of relapse is higher in the postpartum period, but there are conflicting suggestions for women with MS about reducing this risk. Can exclusive breastfeeding alone prevent relapses? How soon after delivery should DMTs be reintroduced? Are any DMTs safe to take while breastfeeding?

For any parent, the first few months after delivery are tumultuous—adapting to a new member of the family is tiring and stressful. These two elements make women with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS) especially vulnerable to a postpartum relapse. While disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) have been shown generally to reduce relapse rates, none of them are indicated for use during lactation. Therefore, the question of when to restart DMTs postpartum remains a difficult one for physicians counseling MS patients who wish to breastfeed their children.

For any parent, the first few months after delivery are tumultuous—adapting to a new member of the family is tiring and stressful. These two elements make women with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS) especially vulnerable to a postpartum relapse. While disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) have been shown generally to reduce relapse rates, none of them are indicated for use during lactation. Therefore, the question of when to restart DMTs postpartum remains a difficult one for physicians counseling MS patients who wish to breastfeed their children.

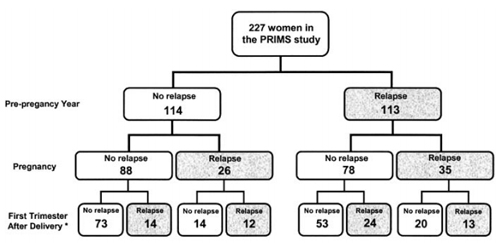

Trying to predict the risk of relapse for any one individual is very difficult. The risk factors for postpartum attacks include the level of disability, the prepregnancy relapse rate (Hughes et al., 2014), and the relapse rate during pregnancy (Coyle, 2014; Vukusic et al., 2004). But even so, relapse rates in the prepregnancy year and during pregnancy combined only predict 21.5% (49/227) of relapses.

Can anyone use the newer studies to help predict which women are likely to relapse?

“Nobody can,” said Kerstin Hellwig, M.D., a senior consultant in neurology at the St. Josef Hospital at Ruhr University in Bochum, Germany, in a conversation with MSDF. “The best study is the PRIMS study. … They found only relapses before pregnancy, relapses during pregnancy, and EDSS [Expanded Disability Status Scale] as a weak predictor.” DMTs were introduced only after this study was conducted, potentially making prepregnancy relapse rates less predictive of underlying disease activity.

“I personally think pregnancy relapses are the strongest predictors,” Hellwig added. “So if I look at my new data, I don't see that prepregnancy relapses are a … significant predictor. But this is mainly because my patients are highly treated.” That leaves only pregnancy relapse rates (a time when most patients are not taking DMTs) as a likely predictor for postpartum relapses.

Reducing the risk of relapse

Until who will relapse during the postpartum period can be reliably predicted, what can be done to prevent relapses becomes the more important question. Some wonder whether breastfeeding can extend the protection that some women experience during pregnancy.

Importantly, breastfeeding is not viewed as having a negative effect on the long-term clinical activity of the mother (Vukusic and Confavreux, 2013; Hellwig et al., 2013; Vukusic et al., 2004). This is based on the PRIMS study (Confavreux et al., 1998), which found that breastfeeding mothers had reduced relapse rates compared to nonbreastfeeding mothers. This data has been interpreted to mean that breastfeeding can provide protection against relapses. But there’s an apparent bias: Women with fewer relapses before and during pregnancy are more likely to choose breastfeeding. So whether breastfeeding actually provides protection remains controversial. Among researchers and clinicians, different factions interpret the current findings in disparate ways: Either breastfeeding is protective, or breastfeeding is not protective in women with high clinical activity.

A group at Kaiser Permanente in California (Langer-Gould et al., 2009) has the strongest evidence to support the view that breastfeeding does provide protection against relapses. In 2009, they showed that among 32 patients and 29 controls, more women who did not breastfeed exclusively had a relapse within the first year after delivery (n = 13 vs. 5 women; p = 0.008) and relapsed earlier than women who exclusively breastfed. What makes this study unique is that the risk of postpartum relapse was not associated with age, disease duration, or DMT use before pregnancy. In fact, exclusive breastfeeding was also protective against relapses in the women who had taken DMTs before pregnancy (n = 22 adjusted HR, 17.7; 95% CI, 2.2-144.5, p = 0.007), and whom the authors presume had higher disease activity.

Soon after the California study was published, an Italian group provided data suggesting breastfeeding is not protective, showing no statistically significant difference in relapse rates between the exclusive and nonexclusive breastfeeding group (Iorio et al., 2009). But the California group pointed out in a published response that this study had low statistical power due to a small sample size (n = 23).

Hellwig’s group in Germany also responded (Hellwig et al., 2009) by including their own data to support the California group’s conclusion that breastfeeding exerts a protective effect postpartum. There was a twofold reduction in the relapse rate in the first 3 months after birth among women who breastfed compared to the nonbreastfeeding group (p < 0.02), but no difference in rates in months 4 through 6 postpartum. The authors attribute this change in significance to the protective effects of DMT use among nonbreastfeeding women. However, they had an extra confounding factor: DMT use was higher before pregnancy among women who did not breastfeed (n = 62) than in those that breastfed exclusively for at least 2 months (n = 151; p = 0.03).

It’s not just the German group’s study that has this confounding factor; a Finnish study published in 2010 that included 61 patients (Airas et al., 2010) reported significantly higher mean relapse rates in the year before pregnancy among mothers who breastfed for less than 2 months (n = 12) compared with those that did for more than 2 months (n = 49, p = 0.04). However, during or after pregnancy, the mean relapse rate did not differ significantly between the two groups (p = 0.602 and p = 0.355, respectively).

A meta-analysis of available data (Pakpoor et al., 2012) from 12 studies published between 1988 and 2011, including the Californian (Langer-Gould et al., 2009), Italian (Iorio et al., 2009), and Finnish (Airas et al., 2010) studies, tried to reconcile their varying conclusions. According to the meta-analysis, women who breastfeed were about half as likely to have at least one postpartum relapse (95% CI 0.34−0.82), even taking into account the study protocol heterogeneity.

To further control for this heterogeneity, the authors grouped the studies with similar protocols and analyzed the groups separately. While prepregnancy relapse rates were not significantly lower in women who breastfed as compared to women that didn’t (mean relapse rate 0.61 vs. 0.82, p = 0.57), women who breastfed were significantly less likely to use DMTs before pregnancy than women who did not breastfeed (p = 0.003).

The use of different DMTs before pregnancy is a significant confounding factor that makes interpretation of the results difficult. The authors of this meta-analysis concluded that their findings did suggest a protective effect of breastfeeding, with the important caveats that the study protocols were heterogeneous and that patient-reported breastfeeding rates might have been affected by recall bias.

Rinze Neuteboom, M.D., a neurologist at the Erasmus University Medical Center in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, is not sure whether breastfeeding is protective. “If you've read all the papers that's produced this protective effect, … some of these studies had problems with the inclusion criteria,” he told MSDF. “If you have a very severe disease course before pregnancy, which is the most clear risk factor for having postpartum relapse, then you are less likely to start breastfeeding.”

Neuteboom is not the only one who’s skeptical of those conclusions. Some argue that separating nonexclusive breastfeeding patients excludes mothers who were exclusively breastfeeding but had to stop due to a relapse, biasing the results (Vukusic and Confavreux, 2013). However, the German group argues against this conclusion. Their data show no difference in postpartum relapse rates between two groups of patients that are seemingly very different—nonbreastfeeding and nonexclusively breastfeeding (defined as at least one breastfeeding meal replaced by formula) mothers—further underscoring the protective effects of exclusive breastfeeding (Hellwig et al., 2012).

However, this German group defined exclusive as 4 months or more of breastfeeding. The exact period of time is the crux of yet another argument that divides those that interpret breastfeeding as being protective versus those that interpret breastfeeding as not being protective. Some argue that by setting the limit at 4 months, they are purposely excluding women with MS that would have a higher risk of relapse. More recently, the California study defined “exclusive breastfeeding” as less than one bottle of formula a day for the first 2 months. They distinguish between this and “nonexclusive breastfeeding,” by any one of three scenarios: breastfeeding for less than 2 months, breastfeeding and supplementing with formula within the first 2 months, or not breastfeeding at all.

The German and California groups agree that defining exclusive breastfeeding rigorously is important because once women start introducing formula or other foods besides breast milk, they experience biological changes. They presented data at a neurology meeting in 2012 (the abstract is available online) in which they showed that in 72 women that were followed for 1 year postpartum, only 11%, or 4/35, of women who breastfed exclusively (for at least 2 months) relapsed during the first 6 months, compared to 32%, or 12/37, of nonexclusively breastfeeding women (p = 0.004). They note that 81% (n = 13) of the exclusively breastfeeding women who relapsed did so after supplemental feedings began.

The California group suggests that only exclusive breastfeeding induces lactational amenorrhea, ovarian suppression, and high prolactin with low, nonpulsatile luteinizing hormone levels (Langer-Gould et al., 2009). Presumably with the introduction of solid foods, which the WHO recommends starting at 6 months, the return of menstruation may coincide with the loss of corresponding protection.

Hellwig tempers the recommendation, saying to MSDF: “If somebody has controlled MS—[defined as] once in a while a relapse, not two relapses per year—then they can breastfeed. I would advise them to breastfeed exclusively … for about 6 months. … After the introduction of supplemental feedings and stopping lactating, then I would recommend to start the MS medication.”

One additional study by Portaccio et al. (2014), published in 2014 from the Italian pregnancy data set, included 350 patients (121 breastfed exclusively) and also found that breastfeeding, consecutively and exclusively for 2 months, had no effect on disability progression (p = 0.403) and did not correspond with fewer relapses after delivery (p = 0.071). This study did not provide a resounding answer (one could even interpret their data showing exclusive breastfeeding to be marginally associated with a lower risk of postpartum relapses), but it did bring up an additional concern. Even if a woman with MS could be classified as belonging to the population with half the risk for relapse, this does not mean that she will not relapse. Again, predicting the disease course for an individual patient is difficult. They showed that 30% of patients experienced relapses in the postpartum period among those who did not have previous clinical activity. In the end, whether a patient decides to breastfeed (whether for the baby’s benefit or the mother’s) is up to the clinician and the patient interpretation of the data.

DMT use immediately postpartum

For women who choose not to breastfeed, taking DMTs soon after delivery is advisable. In fact, most women who do not breastfeed already do so. Why some women choose to wait is likely due to personal choice. Olivier Deryck, M.D., from the neurology department at the AZ Sint-Jan Brugge in Bruges, Belgium, told MSDF, “I have … [a] few patients who did not want to restart [DMT]. They had to stop it for the pregnancy and felt much better without it, and it was very difficult to motivate them to restart.”

But are women putting themselves at risk if they do not start DMT right away?

While taking DMTs can reduce the risk of relapse, for DMTs such as glatiramer acetate (GA) and interferon-β (IFN-β, Avonex, Biogen Idec), this reduction is only by approximately 25% (Beaber et al., 2014; Rice et al., 2001). Additionally, it may take 2 months for DMTs to become effective (Coyle, 2014; Buraga and Popovici, 2014). Hellwig commented to MSDF that there isn't enough evidence to discourage women with MS from breastfeeding, since starting DMTs early after delivery hasn't been shown to decrease the risk of relapse.

A retrospective study by the California group (Beaber et al., 2014), including 80 women who breastfed nonexclusively, found that 67% of women with MS relapsed within 2 years postpartum. Those who were treated within 2 weeks postpartum were more likely to have received treatment in the 6 months before pregnancy. But they found no difference in relapse rates in the first 6 months between women who resumed treatment within a year postpartum (n = 38) or within 2 weeks postpartum (n = 17).

On the other hand, the aforementioned Italian MS center study (Portaccio et al., 2014) found that introduction of DMTs within the first 2 months postpartum was associated with an increase in the mean time to first postpartum relapse from 8.88 months to 10.32 months (log-rank p = 0.006), but not if the cutoff was 4 months, arguing for DMT use as early as possible. In this study, 74 (21.1%) patients started DMTs within 3 months after delivery—with a higher proportion of these having taken some DMT before pregnancy, as in the California study.

Can DMTs be used while breastfeeding?

Given that neither DMTs nor breastfeeding are fully protective against relapses (even in the best case scenarios), could they work in combination? Right now, this is not done. In the 2009 California study, for example, 73% of the women reported not breastfeeding in order to start taking medication to treat MS (Langer-Gould et al., 2009). There are very few published reports of exposure to DMTs while breastfeeding.

Hellwig told MSDF, “Nobody has data. Probably, it's okay to breastfeed under IFN-β or Copaxone [Teva]. But that's very off label, probably in the U.S. even more. Probably it's not okay to breastfeed under any small molecule … which will transfer into the milk and can be ingested orally—even by the baby. … Probably you could breastfeed under monoclonal antibodies too, because they go into the breast milk in a much smaller amount than in the sera, but they cannot be ingested orally.”

The only studies that are available focus mainly on the two classes of DMTs that have been around the longest: GA and IFN-β. Combining all the data from three case reports (Salminen et al., 2010; Fragoso et al., 2010; Hellwig and Gold, 2011), 14 women have been exposed to GA and one woman exposed to IFN-β while exclusively breastfeeding for at least 2 months.

Most of the studies do not report outcomes (Salminen et al., 2010), or if they do, they just say that babies developed normally without describing the criteria used to make this assessment (Hellwig and Gold, 2011). But a study from Brazil followed up at 1 year postpartum with nine patients receiving GA who breastfed for more than 2 months (Fragoso et al., 2010). No developmental defects were reported, with the exception of one child with delayed language, based on the Denver II Developmental Screening Test. They found no difference between pregnancy and postpartum relapse rates, which they attribute to breastfeeding (higher in this study than in the average Brazilian population) and/or GA use.

Whether GA or IFN-β would be harmful if taken by a breastfeeding mother depends on the DMT’s ability to be transported into the breast milk and also absorbed in the gastrointestinal tract of the nursing infant. IFN-β is a large protein (22.5 kDa) without a known transporter, which makes it unlikely to be found in breast milk.

Supporting this notion, Dr. Thomas Hale’s group from Texas Tech University has published a study in which they analyzed the breast milk of six mothers between 1 and 72 hours after taking IFN-β (Hale et al., 2012). In the samples in which he detected IFN-β, the levels were very low: 32.9−179 pg/ml, which corresponds to 0.006% of the maternal dose. The infants in this study did not show any acute adverse effects that might be associated with exposure to IFN-β. There is no similar study for GA, due to the difficulties in detecting this drug—an amino acid polymer—among the components of breast milk, but it is unlikely to be absorbed intact through the gastrointestinal tract (Cree, 2013).

Yara Dadalti Fragoso, M.D., Ph.D., the author of the Brazilian study and a neurology professor at the Universidade Metropolitana de Santos in São Paulo, Brazil, told MSDF: “I think injectable drugs are injectable because they cannot be absorbed orally. Therefore, even if the baby [were] to have some of these drugs in the breast milk, there is little chance the drug would have any effect. As for GA, this may be a good option because its pharmacokinetics is very favorable to a real short life and no accumulation in body tissues.”

Elizabeth Crabtree-Hartman, M.D., an associate clinical professor of neurology and the director of patient education and support at the UCSF Multiple Sclerosis Center, is also not opposed to using GA for the right candidate. However, she brought up an interesting point when she spoke with MSDF about this topic: “I think if we had more options for agents that would be considered safe during pregnancy, it would be a great development for our patients and their families, … especially because it's not uncommon for patients to have breakthrough disease activity on GA.”

Among the other drugs, it is known that fingolimod (Gilenya, Novartis), mitoxantrone (Novantrone), and natalizumab (Tysabri, Biogen Idec) are secreted in milk, but there’s no information regarding dimethyl fumarate (Tecfidera, Biogen Idec). It is less likely that these DMTs will ever be recommended for use in nursing mothers, but more studies are needed, and ultimately the decision is up to the clinician and patient.

Unfortunately, the bottom line is there are still no conclusive studies that can provide a simple guide as to what to do with respect to breastfeeding and the use of DMTs in the postpartum period. The available studies have failed to show a negative effect of breastfeeding, but whether it provides protection against relapses is still controversial. While more studies are being conducted and published, the decision about whether to breastfeed will depend on many factors, including personal patient choice, level of disability, and history of relapses. There are still too few cases of patients taking DMTs while breastfeeding to be able to provide an encompassing suggestion for all patients, but the data seem promising for use of GA and IFN-β while breastfeeding.

Key open questions

- How can the risk of relapses in the first few months after delivery be lowered?

- Is exclusive breastfeeding protective against relapses for all MS patients?

- Is lactational amenorrhea a better predictor of reduction in relapse rates than exclusive breastfeeding? Should this be measured instead of extent of breastfeeding?

- What other biological changes in pregnant or breastfeeding women can be correlated with reduced relapse in the postpartum period?

- Which DMTs can pass into the breast milk and also be absorbed through the baby’s gastrointestinal tract?

Disclosures and sources of funding

Yara Dadalti Fragoso, M.D., Ph.D., reports no disclosures.

Kerstin Hellwig, M.D., received speaker honoraria from Merck Serono, Bayer healthcare, Biogen Idec, Teva Sanofi-Aventis and Novartis Pharma.

Rinze F. Neuteboom, M.D., reports no disclosures.

Olivier Deryck, M.D., has received travel support from Merck Serono, Biogen Idec, Novartis Pharma and Teva and institutional grant support from Merck Serono and has served on a scientific advisory board for Novartis Pharma.

Elizabeth Crabtree-Hartman, M.D., reports having served on advisory panels for Biogen and Novartis.

Comments

Diagnosed with ms in 1995, AFTER giving birth in 1993 (did not breastfeed because uncomfortable after c-section and 10 lb 11 1/2 oz baby boy), I was using DMT Avonex.

I became pregnant in January 2004 (36 years old) and stopped the DMT after consulting with my neurologist.

Baby girl was born in August (6 wks pre-mature) and I breastfed for three months. Breastfeeding was physically and mentally demanding even more so because of the ms.

After three months of breastfeeding, I began DMT again.

I did not experience any noticable exacerbations during the pregnancy and breastfeeding of my baby girl.

There are a few things that I know for certain about ms. One is that this disease, when comparing persons with the same diagnosis, is only simliar by its' name.

My decision to stop ALL pharmaceuticals when I became pregnant was made to protect the new life growing inside me (as I had done so with my first pregnancy, pre-ms). This decision, along with the decision to beastfeed, was made with my husband and under consultation with my neurologist and obstetrician.

We did not refer to any research studies because afterall, multiple sclerosis affects each person differently.