Viral Villain

Risk III: The evidence stacks up against Epstein-Barr virus, but its methods remain mysterious

When considering suspects that might trigger illness, disease detectives often point a finger at viruses and bacteria. MS researchers are no exception. They have scoured the world for possible microscopic troublemakers, including the chickenpox virus, the measles virus, the human immunodeficiency virus, the canine distemper virus, human herpes viruses, various parasitic worms, and the bacteria that cause Lyme disease and pneumonia. However, they have built a strong case against only one microbe, the ubiquitous Epstein-Barr virus (EBV).

Suspicious alliance

About 95% of the world’s adult population carries antibodies against EBV (WHO web page), evidence that these individuals were once infected. Most encounters are asymptomatic, especially those that take place in childhood. EBV infections sometimes cause infectious mononucleosis, also known as mono, particularly in adolescents and young adults who have not previously been exposed to the microbe. Numerous studies from the past 30 years have demonstrated that EBV infections are even more common among MS patients than the population at large (Ascherio and Munger, 2007). “What is striking is that 13 out of 13 studies have found that 99% of MS patients were infected with EBV compared to 90% to 95% of the general public,” says Michael Pender, an immunologist at the Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital in Queensland, Australia. “To me, that suggests that EBV has a unique role in MS.” Correlation does not prove causation, but the more frequently two factors occur together rather than alone, the more inclined investigators are to believe that they interact.

Still, the higher rate of EBV infection in MS patients provides only a modest suggestion that the virus could help spur the disease. Other observations have strengthened this connection over time and have weakened the confounding possibility that people who acquire MS are more susceptible to infections in general. For instance, EBV exposure typically occurs prior to MS, as any true cause must. Furthermore, the association between the virus and MS appears to be dose-dependent. The more anti-EBV antibodies individuals harbor, the more likely they are to acquire MS, according to a report published in October 2011 (Munger et al., 2011). Researchers took advantage of blood samples collected from U.S. military personnel, by selecting 444 samples from individuals who remained healthy long after the sample was collected and 222 who went on to develop MS. They found that those with the highest levels of antibodies against EBV had a 36-fold increased risk of MS compared to those with lower amounts. This dose-response effect suggests that EBV helps trigger MS, says Kassandra Munger, an epidemiologist at Harvard School of Public Health in Boston and the study’s lead author.

A related association exists between MS and mono. This malady, also known as the “kissing disease” because it is transmitted through saliva, is characterized by fever and fatigue and is associated with an increased risk of MS. Individuals who have had the illness are two to three times more likely to acquire MS than are people who encountered EBV but experienced no symptoms (Kakalacheva et al., 2011).

The number of observational studies that link EBV and mono to MS has prompted some researchers to suggest that MS arises from a rare complication that follows an EBV infection. If that’s true, the complication remains mysterious at the moment. “There are a number of theories, but none of them convincingly explain how EBV contributes to MS,” says Sreeram Ramagopalan, a geneticist at the Wellcome Trust Centre for Human Genetics in Oxford, U.K. Studying how EBV might promote MS is difficult, in part, because mice and other animals typically used in experiments don't respond to the virus in the same way that people do. Scientists therefore experiment on human cells in a petri dish, and these cells might react differently than their counterparts in the body. Furthermore, most of these cells come from blood, which is easy to access but cannot necessarily replicate events at the site of trouble in MS. To analyze EBV in the central nervous system (CNS), scientists must lay their hands on spinal fluid from MS patients and healthy controls, or on autopsy brain tissue. This material is not as readily available as blood, and years may pass before researchers can reproduce a finding enough times to demonstrate that their results represent the norm rather than an exception. Moreover, although samples from patients inspire hypotheses about what causes MS, they can’t nail down how the disease began because the biological snapshot they provide was taken long after the illness developed.

Pediatric cases of MS lend strength to the case against EBV, but they also present another kink in the theory that MS begins with a rare complication of an infection. About 10% of children who acquire MS before they turn 10 test negative for the virus. EBV remains a risk factor in pediatric MS because more children with the disease test positive for the virus than do kids in the general population. But the virus’s absence in so many youngsters with the illness makes researchers wonder how accurate the EBV test is, how reliable children’s MS diagnoses are, and how necessary EBV is for MS. Perhaps some children are so susceptible to MS—because of genetic or environmental risk factors—that they don’t require the bug to trigger the disease, says epidemiologist Alberto Ascherio of Harvard School of Public Health.

Timing might matter

Hypotheses abound about how EBV contributes to MS. One theory falls under the umbrella of the hygiene hypothesis, which predicts that infections early in life prepare the immune system to avoid inappropriate responses later. If the notion holds water, the sanitary living conditions of wealthy nations might create microbe-naïve individuals whose immune systems develop improperly as a result—and who are thus especially prone to inflammatory disorders. The distribution of MS around the world fits the idea: MS tends to be more prevalent in developed countries, where only about 50% of children are infected with EBV by age 10, compared to developing countries, where 95% of them are infected by then.

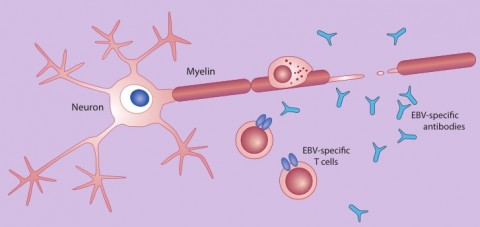

The hygiene hypothesis might account for why more people who have had mono (and likely encountered EBV for the first time after childhood) have a greater risk of acquiring MS than do those who experienced asymptomatic infections as youngsters. Individuals who escaped EBV exposure in youth might have been infected by few pathogens in general. As a result, the thinking goes, they possess particularly jumpy immune systems that overreact to EBV in a way that could stimulate MS. Furthermore, perhaps early infections by EBV in particular help to fine-tune the specificity of immune responses, says epidemiologist Anne Louise Ponsonby of Murdoch Children’s Research Institute in Melbourne, Australia. “If the immune system isn’t well trained early on, it might react to not only EBV but to other proteins that look like EBV in the body,” Ponsonby says. A small fraction—3% to 4%—of EBV-specific T cells extracted from MS patients mistakenly attack human myelin, which forms a protective sheath around nerves and whose breakdown characterizes MS (Lunemann et al., 2008).

The confusion might occur because an EBV protein called EBNA1 and certain myelin proteins share structural similarities. Such cross-reaction might spark the demyelinating nerve damage that characterizes MS.

However, some experts say that 3% to 4% of EBV-specific T cells might not be enough. For that reason, they say the virus must drive the disease through pathways unrelated to molecular mimicry.

Viral hideouts

After the acute phase of EBV infection, the virus takes up long-term residence inside the B cells. At this stage, it remains largely invisible to the immune system, yet it could still promote MS. EBV manipulates cell-suicide pathways within B cells and thus shields infected cells from death. Normally, the immune system kills anomalous B cells that identify the body’s own proteins as invaders, but Pender speculates that EBV infects some of these traitors and protects them as well as normal B cells (Pender, 2003; Pender, 2012). If he’s right, the populations of self-reactive B cells would rise as a result of EBV residence inside them. Eventually, the errant cells might migrate into the CNS, Pender proposes, where they could cause harm by revving up T cells that attack normal proteins—including myelin. EBV-infected self-reactive B cells have not yet been isolated from the blood, spinal fluid, or brains of MS patients. “For my theory to be confirmed,” Pender says, “these cells must be found in the brain.”

Another school of thought posits that self-reactive B cells aren’t essential for EBV-infected B cells to promote MS. Francesca Aloisi, a neuroimmunologist at the Istituto Superiore di Sanità in Rome, Italy, suggests that certain individuals, who are predisposed to an abnormal immune response, harbor EBV-infected B cells that enter the CNS, where they amass and somehow spur damaging inflammation by inciting an immune system response against the virus. The attack might hurt brain tissue, she says, in addition to killing EBV-infected B cells. “The immune system tries to get rid of EBV in the CNS,” she says, “but it does not succeed, and the victim of this continuous attack is the brain tissue itself.” Along those lines, studies that detect higher titers of anti-EBV antibodies in people who later develop MS suggest to Aloisi that certain rare individuals respond especially strongly to the virus in their attempt to control it. Although some steps in the pathway remain unclear, she suggests that these self-defense problems might eventually lead to the neurological troubles of MS. Like other researchers, she adds, she’s trying to connect the dots.

Many research groups have found B cell accumulations in the brain tissue of deceased MS patients and in the fluid-filled space around the outside of the brain, says Timothy Vollmer, a neurologist at the University of Colorado, Denver, School of Medicine in Aurora. However, the idea that these cells harbor EBV remains controversial. Aloisi’s team has detected aggregations of EBV-infected B cells in the brains of deceased MS patients, but other groups have not found evidence of EBV in such cells (Serafini et al., 2007; Franciotta et al., 2008; Willis et al., 2009). Although investigators use similar techniques—namely, immunohistochemistry, in situ hybridization, and reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction—methodological differences can lead to variation in the sensitivity and specificity of these tests, particularly when they apply to tissue that might have been collected and preserved differently after patient autopsies (Lassmann et al., 2011).

The hypotheses that EBV-infected B cells predispose people to MS warrant further research, says neurologist Amit Bar-Or of McGill University in Montreal, Canada (who is an Accelerated Cure Project scientific adviser). But the idea will gain strength only if multiple, independent researchers detect the virus in the brain, he adds. This enterprise has become a top priority for many investigators (Lassmann et al., 2011). If the virus is present, another question will be whether it triggers MS or promotes its activity after onset. Epidemiological studies are consistent with the notion that EBV provides a spark, given that infection generally precedes MS diagnosis.

Another potential mechanism by which EBV might promote MS involves what the virus does outside of the CNS, Bar-Or says. One possibility relates to a molecule produced by EBV called viral interleukin-10 (vIL-10). This immune signaling protein, or cytokine, resembles the IL-10 that humans produce, which quells inflammation. Although the impact of vIL-10 on human immune responses is not fully elucidated, Bar-Or notes, the microbial molecule might compete with human IL-10 and interfere with the human protein’s ability to do its job of quieting inflammation (Hayes et al., 2008). Thus, EBV infection might pave the way toward MS. To examine this hypothesis, Bar-Or suggests that researchers could purify the two forms of IL-10 and compare how they act through the human IL-10 receptor to check whether immune responses are indeed altered.

An unrelated modus operandi for EBV involves silent viruses present within human DNA, called human endogenous retroviruses. HERV gene activity (that of the HERV W family, in particular) has been detected as transcripts and proteins in the CNS—and within MS lesions (Antony et al., 2011). It’s not clear how the genes were stimulated, but a poster presented at the Frontiers of Retrovirology 2011 conference in Amsterdam last October suggests that EBV might contribute (Poddighe et al., 2011).

In addition to the hypotheses mentioned here, investigators have proposed other ideas about how EBV might foster MS. Much work remains in this line of inquiry. "The curse is that the evidence is strong enough to show that EBV is causally associated with MS,” Ponsonby says, “but we don't know whether it's because of the EBV virus itself, an abnormal host response to EBV, or related viruses such as human endogenous retroviruses."

Hesitations on a vaccine

In addition to causing mono, EBV is associated with several cancers, including Hodgkin lymphoma and stomach and nasal cancer. Research on an EBV vaccine has been under way since the 1970s. One vaccine has made it through a controlled, phase II clinical trial in young adults. It didn’t prevent EBV infection, but it reduced the incidence of infectious mononucleosis. In an editorial published last year, NIH leaders called for a phase III trial of the vaccine, which they said might lower the incidence of mono and possibly its associated maladies (Cohen et al., 2011). Other variations of the EBV vaccine are in development, but no one knows how any of them might affect people at risk of MS, and researchers are wary of intervening with EBV. Because infections with the microbe are protective within a certain window—during early childhood, for instance—a vaccine given at the wrong time might increase the risk of MS. Similarly, the vaccine could cause harm if certain people are genetically less able to control an infection, as some research suggests, or if some people have an underlying condition that predisposes them to an abnormal immune response to the vaccine that tilts their bodies toward MS susceptibility. “Until more work is done to understand the implications of an EBV vaccine in people who have other risk factors for MS, we really don’t know if the vaccine will prevent the disease or trigger it in some cases,” Bar-Or says.

Banishing EBV is therefore a questionable goal at the moment, but the evidence linking it to MS onset continues to tantalize researchers. If they can discover its mechanism of action, plans for an intervention might follow. Aloisi and others are approaching the challenge with respect for EBV’s complexity—in particular, the myriad ways in which it modifies the human immune system to survive. “We are dealing with a virus that has coevolved with humans for millions of years, which has very clever ways of existing in its host,” Aloisi says. “There is no doubt this virus is associated with MS, but association studies don’t prove causation. So we have to gather all of the evidence about its behavior in the host and figure out which behaviors are relevant in MS.”

Key open questions

- Mono has been associated with an increased risk of MS; how might the sickness help trigger the disease?

- Are any genetic variations associated with both MS and signs of an abnormal response to EBV, such as elevated anti-EBV antibody titers?

- How do infections with EBV within the first 10 years of life alter the developing immune system?

- Do people who’ve been infected by EBV and/or who’ve had mono harbor EBV-infected, self-reactive B cells? Are these cells in circulation, meaning that they’ve escaped the thymus where they normally would be killed?

- The evidence on whether MS patients carry large numbers of EBV-infected B cells in the brain is conflicting. Can multiple research teams independently confirm EBV infections—with identical, predetermined protocols—using samples from brain tissue in which at least one group has detected large amounts of EBV? If these cells do amass in the brain, how might this accumulation drive MS?

- How is the activity of immune proteins such as the cytokine interleukin-10 altered when viral IL-10 abounds?

Previous article in series: "The Sunshine Suspect"

Next article in series: "Nature, Nurture, and What's in Between"

Image credits

Thumbnail image on landing page. NASA.

Fig. 1. "B cell budding virus," Northen/Wikimedia Commons, 2006.

Fig. 2. Reprinted from Lancet Neurol., vol. 5, J Lunemann, R Martin, C Münz, EBV and MS: cause, consequence, or coincidence, 889-891, copyright 2006, with permission from Elsevier.