The Oligodendrocyte Whisperer

A young researcher’s quest to develop new ways of studying neurodegeneration might yield insights that will benefit MS patients, herself among them

In a darkened room in a fifth-floor Manhattan lab, Valentina Fossati shows off the fruits of her patient labor: a dish of homemade human brain cells. A black headband keeps her long, light hair out of her eyes as she looks down the viewfinder of a microscope. She croons into the plastic petri dish at a clump of cells that has taken her almost two years to goad into existence. As she turns the knobs, they appear. “I love them,” Fossati says. “I talk to them all the time.”

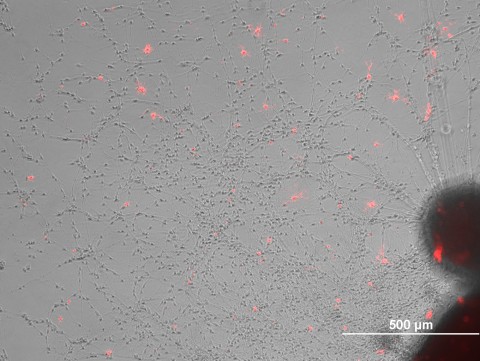

The bright-field setting on the microscope shows many spots and smears—outlines of a variety of cells growing in the dish—but when Fossati flicks on the fluorescence, a breathtaking skyscape of bright white stars pops onto the screen. These spindly cells, aglow from an antibody label, are oligodendrocytes, which enshroud and protect neurons of the central nervous system with their fatty myelin tendrils. Fossati, an investigator at the New York Stem Cell Foundation (NYSCF), has finally figured out how to create them from so-called human induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells—adult cells reverted to a stage of complete immaturity from which they can form any cell in the body. Oligodendrocytes play a central role in multiple sclerosis: The disease spurs a person’s immune system to destroy the cells’ myelin shoots. And yet, little is known about how these cells function—or malfunction—in people with MS.

Fossati aims to change this state of affairs. She is driven by more than scientific engagement: She began studying MS when she learned that she had the illness. Deriving oligodendrocytes and other types of brain cells from MS patients and comparing them to their counterparts in healthy individuals, as her lab has begun to do, will allow researchers to view the disease in a way that has been impossible until now. “I think this could open up a completely new way of studying human brain cells,” she says.

Stem-cell approaches take root

In the almost 150 years since French neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot first characterized MS (Charcot, 1868), most efforts to understand the disease and devise treatments have set their sights on the immune system. By injecting brain peptides or proteins into mice and other animals (see “Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis”), researchers have probed how stirred-up T cells lead an inflammatory assault on the body’s own myelin; studies of the immune system in people with MS have helped illuminate how the disease unfolds. Such work has led to therapies that quell inflammation, and the dozen or so approved treatments for MS work in this way (see Drug-Development Pipeline).

More recently, researchers have begun to focus on the brain-cell destruction that MS provokes. They are searching for drugs that protect neurons and oligodendrocytes from injury by means other than thwarting inflammation, such as by reducing oxidative stress. One particularly promising compound called BG-12, developed by Biogen Idec and approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in March, appears to shield nerves from damage by preventing oligodendrocyte death directly. But overall, studies of neurodegeneration—and how to prevent it—have been stymied by the dearth of good model systems. Oligodendrocytes live deep within the brain, and extracting them for research is next to impossible. Researchers have managed to derive them from neural stem cells, but the process yields only a small number of cells and few labs are equipped to undertake it.

When Fossati began to read the MS literature, she found that the handful of published studies on human oligodendrocytes relied largely on two techniques. In one, researchers study how these cells generate myelin by injecting them into mutant mice such as shiverer, whose neurons are poorly myelinated (Duncan et al., 2011); the experiments, however, are costly, time-consuming, and difficult to analyze. In the other, human oligodendrocytes are cultured in a dish with rodent neurons, which are much easier to grow than human neurons, to examine how they enwrap neurons with their myelin offshoots (Jarjour et al., 2011). On top of the technical difficulties, Fossati says, “most of the community is quite skeptical of the myelination” in both systems because it’s unclear how similar the cross-species process is to the human one. These problems prompted her to ponder alternatives. Wouldn’t it be nice, Fossati imagined, if she could devise a more robust way to study these cells—in a more realistic setting?

When Fossati began to read the MS literature, she found that the handful of published studies on human oligodendrocytes relied largely on two techniques. In one, researchers study how these cells generate myelin by injecting them into mutant mice such as shiverer, whose neurons are poorly myelinated (Duncan et al., 2011); the experiments, however, are costly, time-consuming, and difficult to analyze. In the other, human oligodendrocytes are cultured in a dish with rodent neurons, which are much easier to grow than human neurons, to examine how they enwrap neurons with their myelin offshoots (Jarjour et al., 2011). On top of the technical difficulties, Fossati says, “most of the community is quite skeptical of the myelination” in both systems because it’s unclear how similar the cross-species process is to the human one. These problems prompted her to ponder alternatives. Wouldn’t it be nice, Fossati imagined, if she could devise a more robust way to study these cells—in a more realistic setting?

Just 6 years have passed since researchers first generated iPS cells from human skin cells (Takahashi et al., 2007). The technology is already deemed so important that the researchers who made the discovery—John Gurdon at the University of Cambridge and Shinya Yamanaka at Kyoto University and the University of California, San Francisco—won a Nobel Prize last year. Watching scientists across many disciplines race to derive specific cell types that could act as disease models, Fossati realized that creating MS-specific oligodendrocytes from iPS cells was the perfect approach for filling this crucial gap in the MS research landscape. It would allow scientists to explore how these cells work, what happens when they get attacked, and why they die. Combining them in a culture dish with neurons from the same individuals could provide the first real human model system for studying how myelin does its job. “I know it’s not real remyelination,” she says, in that it is an artificial system, “but it could be enough for testing drugs and for really understanding the mechanisms and principles” underlying these cells’ role in the disease.

Fossati is among the first to apply human iPS cells to MS, but adult stem cells—which can make a more limited assortment of cell types—are already being investigated to treat the disease. In an approach called hematopoietic stem cell transfer, used in patients with blood cancers and, experimentally, in MS patients for whom standard therapies have failed, doctors attempt to interfere with inflammation by suppressing the immune system with chemotherapeutic or other agents, and then injecting the patient’s own hematopoietic stem cells—blood cell precursors—so the immune system can reboot; ideally this process would create new cells that do not attack the nervous system (Saccardi et al., 2012). In a different strategy, researchers who are running about a half-dozen small, early-stage clinical trials around the world are injecting patients with their own mesenchymal stem cells—forebears of bone, fat, and other types of cells—which curb inflammation and appear to protect the central nervous system from damage. These mesenchymal skin-cell descendants most likely exert their beneficial effects by secreting signaling molecules that soothe inflammation and create a microenvironment that spurs natural regeneration (Uccelli et al., 2012).

Ultimately, says Mark Freedman, a neurologist at the Ottawa Hospital Research Institute in Canada, researchers hope to use iPS cells or human embryonic stem (hES) cells—which are equally malleable—to create oligodendrocytes that could be injected into patients to replace those damaged by the disease. “The potential [for iPS cells] is enormous,” Freedman says. “We are in dire search of something that will offer some degree of repair or protection. The idea is to preserve the integrity of some of the system, maybe long enough for the body to repair itself.” In February, Steven Goldman of the University of Rochester in New York reported growing oligodendrocytes from normal (not patient-sourced) iPS cells and injecting them into newborn shiverer mice—the ones whose neurons are poorly myelinated. The cells could myelinate neurons in the animals’ brains. They also boosted survival: shiverer mice normally die by 20 weeks of age, but almost all of the treated mice lived longer than 6 months and some reached 9 months of age (Wang et al, 2013).

Despite this promising result, however, multiple hurdles stand between this therapeutic strategy and clinical reality. For one thing, once a nerve is frayed, a process common in later stages of the disease, remyelination alone probably will not reverse the damage, although it might prevent further insult. For another, rebuilding myelin in a body that carries myelin-reactive immune cells will leave the newly formed coating open to attack. Furthermore, technical issues add to those challenges, Fossati says. No one knows what kinds of safety hazards might arise from injecting iPS cells into the body, for example. And unlike diseases such as Parkinson’s that affect specific brain regions, MS wreaks widespread havoc on the central nervous system. Where, then, would one inject cells?

More immediately, Fossati says, studying homegrown human oligodendrocytes could help researchers answer a host of biological questions. Comparing gene expression in oligodendrocytes derived from the iPS cells of patients and healthy people could point toward hitherto unidentified genetic factors that underlie the disease. Subjecting cells—from patients and controls—to particular conditions could help reveal environmental factors that promote MS. Examining iPS-generated oligodendrocytes along with neurons and astrocytes, glial cells present in large numbers in the brain, could unveil additional mechanisms that contribute to the disease. The system could also be used to zero in on how the immune system perturbs these myelin producers by examining the interaction of patients’ T cells with their own oligodendrocytes at different stages of the disease. But the ultimate goal, Fossati says, is to devise a way to test potential therapies that can protect nerves from being pummeled by the immune system. “The whole mission of my lab is to develop new tools using human cells to conduct drug screening for neuroprotectant molecules,” she says.

Two years ago, researchers in Australia published the first-ever report on neurons, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes generated from iPS cells that had been derived from MS patient tissue (Song et al., 2011). The approach provides a major boost to drug screening as well as a new way to study the biology of the disease, says Claude Bernard, an immunologist and stem cell scientist at Monash University in Australia and the study’s lead author. With patient iPS cells in hand, “we can ask questions that we would never have been able to ask before,” he says. “And because we have now generated many different lines from patients who have different stages of MS—some very early MS, some in remission, some severely paralyzed—we can also look for difference among those patients at the level of genetic makeup. This would not be possible” without iPS cell technology. Bernard’s group is focusing on neurons; so far, the researchers have found that those grown from patient tissue seem to be less excitable than those obtained from identical-twin or sibling controls.

Freedman agrees that the in vitro systems that Bernard and Fossati are creating can provide much-needed insight as well as a testing ground for new drugs, but he cautions that they probably reflect an artificial state. “You’ve isolated the elements to gain insight into what these cells can do,” he says, “but you don’t know whether that potential can be realized” in the wild complexity of the human body.

A personal passion

Fossati planned on a career in science, but she did not set out to study MS. “I never wanted to work on the brain,” she says. “I find the brain extremely complex and scary.” As an undergraduate in Italy, she majored in pharmaceutical biotechnology at the University of Bologna and stayed there to earn her Ph.D. Growing up in the nearby town of Rovigo, she volunteered for years in the hematology ward of a local hospital, and when the time came to choose a lab for her doctoral research, she settled on one that was investigating leukemia and hematopoietic stem cells.

It was 2004; 6 years earlier, researchers at the University of Wisconsin had derived the world’s first hES cells (Thomson et al., 1998), and scientists around the world were intoxicated with these cells’ capabilities. Concurrently, researchers were tapping into the capacity of adult stem cells to specialize into multiple cell types. Fossati began attending stem cell meetings and soon found herself swept up in the excitement of a young and vibrant field. “I just embraced it,” she says.

That first year in graduate school, at a summer course on stem cells at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in New York taught by top researchers in the field, she got to talking with one of the instructors, a young immunologist at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York named Hans-Willem Snoeck. He encouraged her interest in the field, and when they met again in San Francisco the following autumn at the annual meeting of the International Society for Stem Cell Research, he invited her to spend the last year of her Ph.D. in his lab studying B cell development from hematopoietic cells. Fossati jumped at the chance; the funding climate in Italy was dismal, and few other labs were working on stem cells. “I wanted to try the experience of working in a lab where you have all the support—financial especially—to do really good science,” she says. “I was happy to work on anything.”

She planned to learn as much as possible in her brief U.S. sojourn and then return home, but as Snoeck became increasingly interested in bringing human ES cell research into the lab, the timeframe ballooned. “It was supposed to be 1 year, and then it became two, and then three,” Fossati says. The group had begun shifting its attention to the thymus, an immune system organ that trains T cells to distinguish self from foreign antigens. She received a postdoctoral fellowship from NYSCF, which had launched 4 years earlier, to develop a method for regenerating the thymus by prodding mouse ES cells to morph into thymic epithelial cells.

She had little luck devising a working protocol, however. Amid those efforts, personal misfortune stole her attention. She awoke on her 30th birthday with a strange numbness in her leg, which turned into a burning pain that started low and radiated up into her lower back. After excluding other possible diagnoses such as a herniated disc, her doctor ordered a brain MRI. Looking at the spattering of small lesions on the scan, Fossati cried. Another couple of months of follow-up tests confirmed her diagnosis; in March of 2009, her doctor at Mount Sinai’s MS clinic explained that she had clinically isolated syndrome and that her imaging workup showed active as well as inactive lesions. That situation suggested that the current attack was not an isolated incident, and she should start treatment immediately. “The brain was always scary,” she recalls, “but it was even scarier when I saw the lesions in it.”

In her initial despair, Fossati felt the urge to drop everything and return to Italy, where she would be surrounded by family and old friends. Her family, too, urged her to come back, envisioning that she would experience significant disability—much like her mother’s best friend, who has progressive disease and has been using a wheelchair for the past 20 years. After a month on prednisone, however, Fossati’s symptoms subsided and she began to regain her equilibrium. She realized that to reclaim her life and her health, she would have to stare down her fear by learning all she could about the disease. She began reading obsessively about autoimmunity and MS; soon, her scientific curiosity kicked in.

Retelling her story, she seems amazed still at the scant knowledge about a disease that has been studied for so long. She was especially struck by how little she was able to glean about her own prognosis. “In 5 years, you could be in a wheelchair or you could be totally fine,” she says incredulously. Consumer health websites don’t accurately lay out the most basic facts about the condition. MS is an autoimmune disease mediated by T cells, most such sources say, yet as she dove into the literature, she found that researchers have never identified the trigger for the immune system’s self-attack, and they now know that much more than a T-cell response is involved. Conventional wisdom had it that MS affects primarily white matter, but over the last decade researchers have realized that severe atrophy in gray matter occurs as well, for reasons unknown.

As she ruminated on the state of MS research—and on the next step of her career—NYSCF’s director invited her to accept a 5-year start-up fellowship as an independent researcher there. Fossati didn’t hesitate, and she knew immediately that her lab would leave behind her postdoctoral work on the thymus and turn to MS. In a way, she says, shifting her intellectual sights toward her own disease is a way of psychologically handling the uncertainty the diagnosis has brought to her life. But it’s also the most obvious and useful way she could think of to channel her skills. “This is my job—it’s what I know how to do,” she says. “If I can do something, why not do something that is interesting for me?”

Cellular toil

Fossati expected an easy liftoff: A handful of published protocols describe how to coax iPS cells to become oligodendrocytes, and she figured she would use them to make her cells and then begin her studies. The problem was, the procedure took 4 months and didn’t generate enough cells to work with. For the next 2 years, she slogged away, adding a little bit of this growth factor, leaving out a little bit of that growth factor, and peering through the microscope day after day to check whether the tweaks to her recipe were helping. She also expanded her lab, bringing on two postdocs. Eventually, the team cooked up a potion that halved the time and boosted cell yield.

Fossati, who is 34, exudes elegance, from the black pencil skirt peeking out from beneath her lab coat to the loose silver bracelet that sparkles between the white coat’s cuff and the blue latex gloves she slips on to pull a tray of iPS cells out of the incubator. “The cells, they always behave as they want,” she says in a lilting Italian accent. And they need a lot of attention. “It’s worse than having a dog.” Every day, she or one of her postdocs, Marco Calafiore and Panagiotis Douvaras, must change the medium in each dish and adjust the recipe of growth factors that keep the iPS cells moving toward an oligodendrocyte identity. ”Sometimes they just decide they will die,” she says, “and you have no idea why.”

Fossati, who is 34, exudes elegance, from the black pencil skirt peeking out from beneath her lab coat to the loose silver bracelet that sparkles between the white coat’s cuff and the blue latex gloves she slips on to pull a tray of iPS cells out of the incubator. “The cells, they always behave as they want,” she says in a lilting Italian accent. And they need a lot of attention. “It’s worse than having a dog.” Every day, she or one of her postdocs, Marco Calafiore and Panagiotis Douvaras, must change the medium in each dish and adjust the recipe of growth factors that keep the iPS cells moving toward an oligodendrocyte identity. ”Sometimes they just decide they will die,” she says, “and you have no idea why.”

No one knows why oligodendrocytes are particularly hard to produce from iPS cells, says James Goldman, a glial cell biologist with a lab across the road at Columbia University. He and Fossati chanced upon each other when he, also seeing the need for research on human oligodendrocytes, sought out NYSCF in the hope of starting exactly the project she had thought up. The two are now collaborating. “It’s been frustrating, but if you think something is worth it, you are willing to put up with some annoyances,” Goldman says.

With a solid differentiation protocol in hand, Fossati's lab has begun characterizing oligodendrocytes derived from skin samples obtained from patients at the Tisch MS Research Center of New York. Collaborating with Saud Sadiq, who directs the center, Douvaras is examining cells from four people with relapsing-remitting MS, four with primary progressive MS, and four with secondary progressive MS—plus control subjects, to look for any obvious differences. Do they express different sets of genes, for example, or have obvious defects in intracellular structures? Calafiore, meanwhile, is conducting parallel studies in neurons derived from the same patients. “Some people believe that MS could have a hidden neurodegenerative process that is independent from immunity,” Fossati says. Robbing patients’ neurons of oxygen or hitting them with free radicals—events they might experience within an MS lesion—might reveal intrinsic differences between MS patients and healthy individuals. “It would be fantastic if we could find something that was specific to primary progressive patients,” she says, “something we could use as a marker” to identify this particularly destructive form of the disease.

The team is also trying to raise oligodendrocytes and neurons in the same dish to push the cells to remyelinate so they can realize Fossati’s main goal—to use these co-cultures as test beds for potential drugs that would stem nerve damage and possibly allow the body to heal. The group recently received funding to conduct a preliminary screen for small molecules that might block neurodegeneration. NYSCF is setting up its own equipment to conduct such work, but until that system is up and running, Fossati will be collaborating on the work with Paul Tesar, a stem cell scientist and geneticist at Case Western University in Cleveland, Ohio. “Perhaps,” she says, “we can find a drug that is able to wake up oligodendrocyte precursor cells in the brain and help them differentiate”—thereby replacing destroyed myelin.

As for the state of her own myelin, Fossati considers herself lucky. After her initial MS symptoms were subdued, she stopped treatment and has not experienced further flare-ups. “When it happens to you, you immediately go, ‘Oh my god, this is a disaster,’ ” but “you can actually have the disease and have a normal life,” she says. “If people don’t talk about [that possibility], then you don’t know.” She makes herself available to people back home who have recently been diagnosed. “I discovered friends who I didn’t know have MS, because especially in small towns, people don’t want to talk,” she says. “I think we should talk way more, in general, about diseases. I always believed that the best way is to flaunt it.” She is quick to tell collaborators that she has MS—in part to explain the abrupt switch in research topics she made when she started her lab at NYSCF. But that candidness also stems from the same source as her persistence at the lab bench and her delight at the view down the microscope: a conscious decision to shine a bright light on MS.

Key open questions

- Do oligodendrocytes derived from iPS cells of people with MS differ from oligodendrocytes derived from healthy controls, and if so, how?

- Do T cells and oligodendrocytes from people with MS interact differently than T cells and oligodendrocytes in people without the disease?

- Can iPS-derived oligodendrocytes form functional myelin?

- Will drug compounds that regenerate iPS-derived oligodendrocytes in culture help reduce the symptoms of MS?

Image credits

Images courtesy of Valentina Fossati.

Gazette des hopitaux, Paris 41: 554–55.