Interferon β and Glatiramer Acetate Are Clinically Similar, Says Cochrane Meta-Analysis

A review of five head-to-head clinical trials suggests that interferon β and glatiramer acetate are clinically similar disease-modifying therapies with some differences in MRI outcomes that clinicians should consider

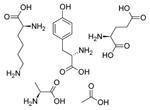

A recent review from the Cochrane Collaboration looked at the efficacy of interferons β (IFNs β) and glatiramer acetate (GA) for treatment of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS) in five head-to-head clinical trials (La Mantia et al., 2014). IFNs β and GA are the two oldest disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) for RRMS. Both were discovered 15 years ago and both are administered via injection, but it’s not clear if there are clinical differences between the two therapies or if one is superior to the other.

A recent review from the Cochrane Collaboration looked at the efficacy of interferons β (IFNs β) and glatiramer acetate (GA) for treatment of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS) in five head-to-head clinical trials (La Mantia et al., 2014). IFNs β and GA are the two oldest disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) for RRMS. Both were discovered 15 years ago and both are administered via injection, but it’s not clear if there are clinical differences between the two therapies or if one is superior to the other.

The researchers examined 404 records of trials of IFNs β-1a and -1b and GA. After funneling all the records through an exhaustive set of criteria they narrowed their review down to five studies. The result was a meta-analysis of 2858 patients with RRMS randomly assigned to either IFN treatment (1679) or GA treatment (1179). The researchers did not control for gender, age, or race, but the participants had to have an Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) score between 0 and 6.0 and be on the treatment for at least 3 months.

For primary outcomes, the team analyzed the number of patients who had a relapse within 1 or 2 years after follow-up. They also looked at the number of patients whose condition worsened, classified as an increase of at least 0.5 points on the EDSS for patients with a starting score of 5.5 or higher and an increase of at least 1 point for patients with a score of 5.0 or lower. Finally, they assessed clinical safety outcomes by the number of patients who dropped out due to adverse effects from treatment.

The researchers also analyzed a set of secondary clinical outcomes including time to first relapse after the start of the study, frequency of relapse, and the percentage of participants free of disease activity. They also looked at MRI outcomes in T2-hyperintense and T1 lesions.

Generally, the researchers found no statistically significant differences between IFNs β and GA in primary or secondary clinical outcomes, though one of the studies suggested that GA was more effective at reducing the relapse rate at the 3-year follow-up. The participant dropout rate was also similar between the two treatments (RR 0.95, 95% CI 0.64 to 1.39). The team was not able to measure quality-of-life outcomes due to a lack of data.

MRI outcomes varied more. The number of active T2-hyperintense lesions was significantly lower in IFN β-treated groups than in GA-treated groups at 6 months (mean difference -0.86, 95% CI -1.32 to -0.40; P value 0.0003), but there were no differences at 12 and 24 months. The researchers also found significantly less increase in T1 lesion volume in IFN β-treated patients at 24 months (mean difference -0.20, 95% CI -0.33 to -0.07; P value 0.003). Interestingly, the team also found significantly greater loss of overall brain volume in the IFN β-treated group (mean difference -0.12, 95% CI -0.23 to -0.01; P value 0.04).

Limitations

The authors cautioned that the data were quite heterogeneous, making it unclear whether the differences in MRI outcomes are due to the treatment or are artifacts of the review process.

The study reported that all the trials in the meta-analysis were at a high risk for attrition bias, which is the potential for results to be skewed by the data lost from patients who drop out of the trial. Some studies also had higher risks for selective reporting biases and issues with proper blinding as well.

The authors also mentioned that they were unable to assess quality-of-life measures in the patients involved in the studies, saying this limitation “impaired the possibility of adequate evaluation and comparison of the relative tolerability of different DMTs in terms of patient-reported outcomes.”

Conclusions

The authors suggested that based on their evidence, clinicians should feel able to prescribe either IFNs or GA to patients, but they should consider the MRI and clinical outcomes of both therapies.

The authors also proposed that future clinical trials should be clearer in their reports of various results. Specifically, they requested that researchers report the reason for patient dropouts, so future meta-analyses might find patterns in that data. MRI reports also tend toward heterogeneity and a lack of clarity, and there should be a more uniform protocol for the acquisition and reporting of images, the researchers said.

Key open questions

- How can researchers standardize their data acquisition and presentation to aid in future meta-analyses?

- What are other limitations of this study that the authors may not have reported?

- What other therapies for MS might benefit from this sort of meta-analysis?

Disclosures and sources of funding

La Mantia et al. received funding for this study from Cochrane Multiple Sclerosis Group and The Cochrane Collaboration. Authors Rovaris and Weinstock-Guttman have participated in meetings and trials sponsored by large pharmaceutical companies. Aaron Boster, who commented on this study but was not involved in it, said he has received compensation for participation in consulting and advisory boards from Teva, Biogen, Novartis, Genentech, and Medtronic.

Comments

This is a Cochrane review and they don’t accept the vast majority of clinical data. They only accept what they consider is the purest and cleanest data, which is helpful but there’s a lot that they’re leaving out. That said, I think the take-home message here is that these two treatment classes have rather similar efficacy profiles. But we need to consider the fact that there are many more disease-modifying therapies than just these two.