Cognitive Reserve in MS: Life Experiences Matter

Memory, brain speed stoked by stimulating activities

More than half of all people with multiple sclerosis (MS) feel a drop in their ability to think quickly and clearly and to remember easily, but like so many aspects of MS, the cognitive impact is unpredictable. Some people lose brainpower early, while others tolerate advanced disease without noticing much effect.

In a new study testing two ways the brain may cope with MS-related changes, researchers found that both bigger heads and more intellectually enriching leisure activities, such as reading and blogging, may protect against cognitive impairment (Sumowski et al., 2013).

Like height and eye color, people have little say in their genetically determined head size. But the results suggest that people may be able to boost their mental acumen above and beyond the extra capacity of a bigger brain to withstand disease damage. The paper, published online 10 May 2013 and in the 11 June 2013 issue of Neurology, extends evidence about the protective effect of a large brain to MS and shows that size alone doesn't tell the whole story.

The two mechanisms seem to protect different features. Big brains explain about 12% of the overall difference in mental functioning among people with similar disease status, but accounted for about 19% of the difference in brain speed or efficiency. Leisure activities, on the other hand, covered about 13% of the difference in overall cognitive functioning, but accounted for about 12% of the difference in memory and 8% of speed.

"It's very provocative and worth thinking about how this could be applied clinically," said Peter Arnett, Ph.D., a neuropsychologist at Penn State University, in an interview with MSDF. "You're either lucky to be born with a big brain or not. You don't have any control over that. But people have a choice to engage in cognitively stimulating leisure activities to build a cognitive reserve that might buffer them against a decline." Arnett was not involved in the study.

Brain Reserve and Cognitive Reserve

The two related theories tested in the new study first arose in Alzheimer's disease to explain how one person can appear unaffected by disease-related brain changes, while the same amount of apparent pathology can tip another into dementia (Stern, 2012). The concept of "brain reserve" came first. It suggested that a larger brain could abide more damage before it hit some critical threshold for symptoms to appear, perhaps because of extra neurons or synapses or the underlying biology. Brain size is mostly determined by genetics, but the loss of brain volume may be slowed by exercise (Voss et al., 2011) and, in MS, by some disease-modifying therapies, the study authors said.

A second concept, known as "cognitive reserve," has been proposed to reflect how people with higher education and other markers of intellectual activity seem more resistant to dementia. Cognitive reserve may contribute to functional or compensatory mechanisms that may also delay the onset of symptoms from disease-related brain changes. In some views, cognitive reserve also includes expansion of neural network or neurogenesis from intellectual or physical training.

"Brain reserve and cognitive reserve are the most important concepts in MS in the last 20 years," said Timothy Vollmer, M.D., a neurologist at the Rocky Mountain Multiple Sclerosis Center in Aurora, Colorado, in an interview with MDSF. "This paper is one of the strongest papers in actually quantifying the impact of genetically and biologically determined brain size, as well as clarifying the role of cognitive reserve," said Vollmer, who was not involved in the study. "By living an active lifestyle, including learning and physical activity, you can further expand your cognitive reserve."

For the new study, first author James Sumowski, Ph.D., a neuropsychologist at the Kessler Foundation Research Center in West Orange, New Jersey, and his colleagues have spent 4 years documenting that higher cognitive reserve seems to protect mental functioning in people with MS, as it does in Alzheimer's and aging.

"We don't know what this entity called cognitive reserve actually is," said co-author Victoria Leavitt, Ph.D., a neuropsychologist at the Kessler Foundation, in an interview with MDSF. "It's a nebulous entity. The point is, something in the brain confers a beneficial protective influence" in response to life experiences.

Missing from the story until now is how much of the apparent cognitive protection stems from brain reserve rather than cognitive reserve. Sumowski and his colleagues have been measuring cognitive reserve by vocabulary, educational level, and intelligence, all of which are also linked to brain size.

"The ultimate goal of all this is to find a way to bolster reserve," he said. "Is there a lifestyle change we can encourage to make it less likely people will develop cognitive problems in the future? Remaining cognitively active or becoming cognitively active is likely to be one of those factors."

Study Details

For this study, Sumowski and his colleagues evaluated data collected by the Italian research group headed by Massimo Filippi, M.D., a neurologist at the San Raffaele Scientific Institute in Milan, Italy. The study enrolled 62 people with MS (30 women), with an average age of 44 years and average education just past high school (13 years). Two-thirds of the people had relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS). The others were diagnosed with secondary progressive MS (SPMS).

To establish the cognitive outcome, the researchers ran two standard tests to measure brain processing speed and four tests to assess learning and memory in all the participants.

"When people with MS talk about the cognitive problems they're experiencing, they say: 'I can't handle life the way I used to,' 'I can't multitask,' and 'I can't keep up with my work,' " Leavitt said. "It's important to note that it's cognitive impairment [rather than physical disability] that takes people out of the workplace, and/or fatigue. It's hard to pin down where fatigue lives in the body, but we think processing speed may be involved."

The researchers estimated the extent of disease in each person's brain by MRI scans to detect lesions and atrophy. They used intracranial volume as a marker of maximum lifetime brain volume. "The space inside your skull essentially is determined by how large the brain grows," Sumowski says. "Based on developmental research in healthy people, this tells us how big the brain grew at its largest point." Brain volume peaks by early adolescence, after which the head size holds steady while the brain shrinks, he says.

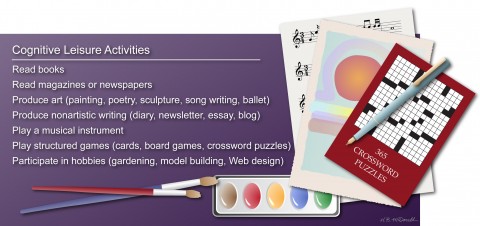

To estimate cognitive reserve, they surveyed the study participants for how much time per year, month, week, or day they had participated in cognitive leisure activities before diagnosis (see table). Sumowski developed the questionnaire as a more widely representative assessment of intellectual engagement than formal education.

As expected, they found that a large brain on average reduces the effect of lesions, accounting for about 12% of the difference in overall cognition, when the researchers controlled for cognitive reserve measures. Cognitive leisure activities were at least as beneficial, explaining about 13% of the average difference in cognitive outcome measures.

"The cognitive reserve story is nice, because it's optimistic," Leavitt says. "It's inspiring. It means we can likely impact our own fate by choosing to do something intellectually enriching."

Intriguingly, the two types of reserve seem to be protecting different abilities, the researchers found. Brain reserve seems to protect against speed deficits and cognitive efficiency, but not memory problems, Sumowski says. Cognitive reserve protects more against memory problems.

The results are consistent with the Alzheimer's and aging literature on brain reserve, which links bigger heads to cognitive efficiency and brain atrophy to declines in brain speed, not memory, they write in the paper.

"It's interesting that the same factors appear to be protective in two distinct diseases," said Catherine Roe, Ph.D., a cognitive researcher at the Knight Alzheimer's Disease Research Center at Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri, in an interview with MDSF. Roe was not involved in the MS study. In a recent study, Roe found a correlation between education, a big brain, and resistance to dementia in people with early biomarkers of Alzheimer's in their cerebrospinal fluid.

Sumowski suspects that the cognitive-enhancing life experiences may be working through the hippocampus, a part of the brain that can develop new neurons and has been shown to enlarge in animals exposed to enriching environments. Aerobic exercise also increases hippocampal volume with accompanying memory improvements, according to preliminary results of a randomized controlled trial of people with MS that Sumowski and Leavitt reported at the March 2013 meeting of the American Academy of Neurology in San Diego, California.

The apparent independent protection provided by cognitive reserve is promising, but the authors and other experts consulted for this article added two major cautionary notes. "It's an observational study, so we cannot infer causation yet," Sumowski said. "We need to do this work longitudinally, to see if higher reserves are associated over time in the same person."

It would also be interesting to see whether people with cognitive difficulties would improve over time with an intervention of cognitive leisure activities, Arnett said. And it may be challenging to find enriching leisure activities for people with MS, whose physical disabilities may limit their actions, he said, citing one patient who had to stop playing the guitar because of numbness in his fingers and the loss of motor control.

The potential implications extend even further, adding support to a new way of thinking about MS. "Brain reserve unifies MS,” Vollmer said. “I would argue that the onset of progressive disease doesn't represent a change in the pathology, but reflects the loss of brain and cognitive reserve. It refocuses attention away from relapses and toward preserving brain volume [slowing atrophy] as the therapeutic goal." Vollmer said that he and his colleagues are preparing a detailed paper outlining this new theoretical framework for MS.

So far, there is no evidence that remaining cognitively active will slow down the underlying biological pathology and progression of aging, Alzheimer's, or MS, Sumowski said. But a prescription to read good books and master new musical pieces may make it easier to function with advanced disease.

Key open questions

- What are the underlying neural mechanisms explaining the associations between brain and cognitive capacity and a patient’s ability to compensate for MS-associated pathology?

- Can people with MS preserve their remaining brain reserve and protect cognitive efficiency with disease-modifying therapies that slow brain volume loss and by maintaining a "brain healthy" lifestyle, such as aerobic exercise?

- As the disease progresses, can people with MS slow their cognitive decline and memory with cognitive leisure activities, such as solving crossword puzzles and reading books and magazines?

- Do measures of cognitive reserve in MS have potential to become a more sensitive measure of disease progression than motor deficits?

- How does the physical and cognitive decline of people with MS affect their ability to engage in activities that may protect them from further impairment?

Image Credit

Infographic by Heather McDonald.

Disclosures

The study was funded in part by the National Institutes of Health. J. F. Sumowski, V. M. Leavitt, and G. Riccitelli reported no disclosures. M. A. Rocca reports receiving speakers’ honoraria from Biogen Idec and Serono Symposia International Foundation and research support from the Italian Ministry of Health and Fondazione Italiana Sclerosi Multipla. G. Comi reports receiving compensation as a consultant, speaker, or scientific advisory board member with Teva, Merck Serono, Bayer Schering, Novartis, Sanofi-Aventis, and Biogen Dompé. J. DeLuca reports salary support through compensation to the Kessler Foundation Research Center from Biogen Idec and serving as a consultant for Biogen. M. Filippi reports connections with Teva, Genmab A/S, Bayer Schering, Biogen Dompé, Merck Serono, and Fondazione as a consultant, as a member of scientific advisory boards and speakers bureaus, and as a recipient of travel funding and research support.