Study Probes “No Evidence of Disease Activity” in MS Patients

“No evidence of disease activity,” or NEDA, means no clinical or MRI disease activity. As a treatment goal, the first study of NEDA in a “real-world” patient cohort shows plenty of room for improvement and a glimmer of hope.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) may as yet have no cure, but that’s not stopping a push to make remission a standard of care. The proposed goal is called “no evidence of disease activity,” or NEDA (pronounced NEE-dah). It means no relapses, no disability progression, and no new or enlarging lesions on MRI. It may be difficult to achieve, according to a recent study that proponents call a starting point.

In more than 200 people followed for 7 years or more, NEDA status plummeted over time. At 1 year, 99 (46%) met the NEDA criteria. At 2 years, 60 (27.5%) sustained NEDA. At 7 years, only 17 (7.9%) people with MS or the one-time relapse known as clinically isolated syndrome showed no signs of clinical or MRI disease activity (Rotstein et al., 2014). The findings were published online December 22 in JAMA Neurology.

The findings show that NEDA may be a clinically meaningful, realistic, and achievable goal with potential long-term benefit for patients, neurologist Rob Bermel, M.D., told MSDF. Bermel has organized two MS expert consensus summits on bringing NEDA into the clinic and is giving a related talk on January 23 at the “Breakthroughs in Neurology” meeting of the American Academy of Neurology in Phoenix, Arizona. He was not involved in the study.

“This is the first real-world look at NEDA in clinical practice,” said Bermel, medical director of the Mellen Center for MS at the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio. “As a research field, we need to advance the therapeutics,” Bermel told MSDF. “But in the meantime, for patients here and now, this school of thought would say, using the medications we have and the tools we have—MRIs, clinical visits, and exams—can we achieve better outcomes in more patients in this treat-to-target approach?”

NEDA status at 2 years bodes well for a 7-year remission, with about a 78% positive predictive value for no disease progression, the study found. And those without NEDA at 2 years were not doomed, with only a 43% negative predictive value at 7 years.

“It shows we have a ways to go, but it gives us a benchmark,” senior author Howard Weiner, M.D., told MSDF. The patients were selected from the 2,200-patient Comprehensive Longitudinal Investigation of Multiple Sclerosis at Brigham and Women’s Hospital (CLIMB) cohort study. Weiner anticipates following up over time.

Why NEDA now?

The discussion about NEDA reflects major shifts in the treatment approach for MS made possible by more effective drugs. Depending upon the country, up to 12 disease-modifying therapies have been approved with eight distinct mechanisms of action. Treatment philosophy increasingly appears to be dominated by a preference for aggressive early management in an attempt to prevent the irreversible damage that leads to disability.

“Some critics would argue that NEDA is too stringent treatment target and we should not aim for it but instead settle for a MEDA (minimal evidence of disease activity),” wrote neurologist Gavin Giovannoni, MBBCh, Ph.D., of Barts and The London School of Medicine and Dentistry on the Multiple Sclerosis Research Blog. “I am against the latter, particularly since we know that a lot of disease activity occurs below the threshold of our current measurement tools and, once damage accumulates in MS, it tends to be irreversible, i.e. time is brain. In addition, if we have more effective treatments and if the disease is not controlled on less effective DMTs, why wait to offer the patient the option of escalating to more effective treatments? I envisage some patients saying no, as the risks associated with the more effective treatments may be unacceptable, [and] some may want to be extending or starting a family and prefer the DMTs with a good safety profile in pregnancy, and others may not accept NEDA as a treatment target.”

“As they come down the pike, the newer medicines do a better job,” neurologist Michael Racke, M.D., told MSDF. Racke and Jaime Imitola, M.D., both of Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, co-authored an editorial accompanying the JAMA Neurology study (Imitola and Racke, 2014). “As a field, we are improving. On the flip side, we don’t have any cure. At least now we’re having the conversation that our goal is to stop disease activity.”

“As they come down the pike, the newer medicines do a better job,” neurologist Michael Racke, M.D., told MSDF. Racke and Jaime Imitola, M.D., both of Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, co-authored an editorial accompanying the JAMA Neurology study (Imitola and Racke, 2014). “As a field, we are improving. On the flip side, we don’t have any cure. At least now we’re having the conversation that our goal is to stop disease activity.”

NEDA is becoming an important measure in clinical trials under various names, including “disease-free activity” and “no evidence of detectable disease,” but it is not a primary outcome recognized by regulatory authorities. Clinically, neurologists have borrowed the term from rheumatology. There, “disease-free status and remission have been implemented and accepted as goals for clinical trials and for patient care,” Imitola and Racke wrote.

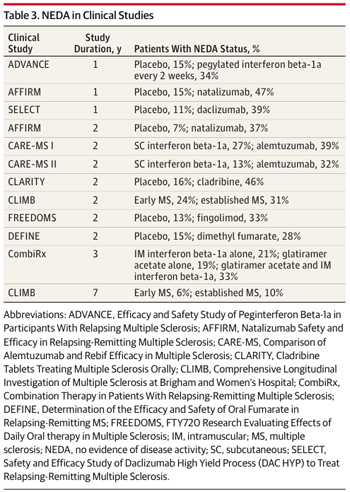

In post hoc analyses of new drug trials in MS, the percentage of patients with NEDA in the first 2 years has varied from 28% to 42%. “NEDA is an ambitious but necessary benchmark, and the current results offer a humbling reminder of the efficacy of today’s therapies,” wrote Imitola and Racke. For example, the most aggressive and risky treatment, autologous stem cell transplant, induced sustained remission in only 75% of patients for 3 years, according to a study published online by JAMA Neurology on the same day as the NEDA study (Nash et al., 2014). Racke is a co-author of that stem-cell study.

The central question in MS

In contrast, almost half of the 200-plus patients in the NEDA study were enrolled between 2000 and 2005, before most of the new drugs were available. More than half of those who sustained NEDA at 2 and 7 years had no treatment at their first visit. The authors found no differences in NEDA status between patients with early or established MS. The study did not stratify NEDA by the various therapies due to small numbers of patients in each treatment group, the authors wrote.

“We’re really asking the central question in MS: Can we shut down the disease?” said Weiner, director of the Partners MS Center at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. “We understand the disease well enough and we have enough drugs and measures to say this is a goal we can work toward. If you talk about diseases like Alzheimer’s and ALS, there are no treatments. You wouldn’t even think about [NEDA].”

Many questions remain about NEDA, including how to measure it and if the measure will really help patients. For example, brain atrophy is correlated with long-term outcomes and is not now included in NEDA. Also, NEDA depends greatly on how well the various tools measure disease activity. The study used a 1.5-tesla machine for the MRI. A 7-tesla machine might have detected more disease activity.

NEDA was adopted for rheumatoid arthritis after a study showed much better outcomes in patients randomized to a treat-to-target arm, compared to those managed with the same drugs by standard physician practice (Grigor et al., 2004). Bermel said a similar study in MS could be launched now.

Key open questions

- What variation of the NEDA status might be acceptable in MS?

- During what period would NEDA be an acceptable standard?

- What timelines and measurement tools should define NEDA?

- What steps can clinicians take to implement NEDA in the clinic?

- If NEDA is not achieved, is low evidence of disease activity acceptable?

Disclosures and sources of funding

Various authors of the NEDA study reported receiving research support from the Multiple Sclerosis Society of Canada, Merck Serono, EMD Serono, and Novartis and serving as consultants for, speaking for, and serving on the scientific advisory boards of companies including Biogen Idec, Novartis, EMD Serono, Teva Neurosciences, GSK, Nasvax, Xenoport, Genzyme, and Sanofi-Aventis. Merck Serono provided partial financial support for data collection and reviewed the manuscript.

Gavin Giovannoni, MBBCh, Ph.D., is a member of the MSDF Scientific Advisory Board.

Additional reporting from Heather McDonald and Hollie Schmidt.

Comments

MRI's of my brain have shown no new lesions and no active lesions.

Perhaps this should be GREAT news, but this just means my brain has shown no new lesions and no active lesions.

The CNS includes the spine, where I also have lesions, yet my neurologist does not pursue routine testing.

Are there additional areas in the body where demyelination occurs? Perhaps these areas, if they exist, should also be routinely tested.

NEDA seems to be, at best, a marketing tag line for pharmaceutical companies to help promote their DMT's.

Using NEDA additionally gives a person with MS a false sense of relief because no one has nor can predict this disease's progression.

I think NEDA is laudable but the results are misleading, particularly in phase 3 clinical trials across all, if not most, newer MS drug studies. No particular mention is ever made about how race affects drug responsiveness (MRI criteria, disability) or how patients with EDSS between 3 and 5 fare, over time. Predictably, NEDA criteria are met early and not as the EDSS begins to climb between 3 and 5, where patients probably stay the least of time on the EDSS scale of disease progression. Till such time as studies fail to report data when EDSS begins to worsen (particularly when in the mid-range), physicians will continue to flounder in the dark as to how to approach NEDA from a disability perspetive. As well, EDSS needs to be replaced, given its inherent flaws.

Secondly, clinically isolated syndrome (CIS) diagnostic criteria ignore patients who do not fit the MRI criteria for diagnosis. What happens to that cohort of patients over time ? Are we not missing an opportunity to treat MS (at the CIS stage) particularly when everyone in the MS world is aware that axonal loss begins early when patients who do not fit the MRI criteria are not defined as CIS ? This could prove critical since NEDA is best achieved at the CIS stage, if one considers disease pathology but what if patients are not even diagnosed since they do not even meet CIS criteria ?

With two major flaws in the system as described above, NEDA, while elegant and simplistic, is riddled with flaws when it matters the most. It is time to redifne how phase 3 clinical trials' data are drawn out and also to look at how CIS diagnostic criteria are defined. Another key query is equally important - perhaps 20-30% of University level programs do not even have an MS fellowship trained neurologists to begin with - how then, do general neurologists approach NEDA at the University level where concepts are supposed to be put into action ? One would suspect that NEDA to a general neurologist would probably be an alien concept.

Hopefully, there will be stragies developed in the MS world by the bigwigs who direct MS care to take it to a different level. To cite another model, tPA treatment for stroke could become treated in the field by EMS personnel. That is early treatment and a successful one if ever there was one (even if overtreated).

Jagannadha Avasarala, MD, PhD

Greenville Health System