Azathioprine: Old Drug, New Data

Azathioprine may be as effective as interferon β in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis, a noninferiority trial suggests

Call it That ’80s Drug. Azathioprine (Immuran and others), a generic immunosuppressant, has been used off-label to treat multiple sclerosis (MS) for more than 40 years. It was largely abandoned as a first-line therapy in many countries in the mid-1990s when the β interferons ushered in a new generation of blockbuster MS therapeutics (Filippini et al., 2013).

Now, new findings may reposition azathioprine (AZA) as an inexpensive treatment option for relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS), especially for people without access to the newer and more expensive drugs. A randomized multicenter clinical trial suggests that the generic drug is at least as effective in reducing both relapses (the primary endpoint) and new brain lesions (the main secondary outcome measure) as interferon β-1a (Avonex, Biogen Idec; Rebif, Merck Serono) or interferon β-1b (Betaferon, Bayer).

Using a noninferiority design, the study is the first to directly compare azathioprine to β interferons. The findings were published November 17 in PLOS ONE by Luca Massacesi, a neurologist at Careggi University Hospital and the University of Florence, Italy, and his co-authors (Massacesi et al., 2014).

“A feasible alternative”

“This study is very valuable,” said Jiwon Oh, M.D., Ph.D., a neurologist at St. Michael’s Hospital and the University of Toronto in Canada, who was not involved in the study. “It’s a feasible alternative to help control disease when existing conventional treatments are prohibitive because of the cost.”

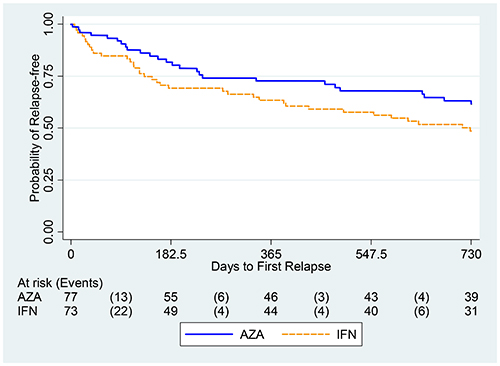

The study started with 150 people with more than two relapses in the past 2 years. The annualized relapse rates were 0.26 in the AZA group and 0.39 in the interferon group, the researchers reported, based on calculations with both the 127 individuals who completed the 2-year study and the original 150 enrolled. The AZA-to-interferon rate ratio was 0.67, representing at least 75% of the effect of interferons compared to placebo.

AZA lacked a modern assessment of brain lesions and relapses until this study, the authors wrote in the paper (Massacesi et al., 2014). It was tested in the 1980s in trials that mixed all kinds of MS cases together in an era before magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was standard. In the new study, the ratio of annualized new T2 and combined new and enhancing lesion rates, as well as accumulating gadolinium-enhancing lesions, were comparable, Massacesi said. Of 122 patients given a baseline MRI, only 97 completed the follow-up—82% in the AZA group and 77% in the interferons.

Beyond the new evidence, Oh told MSDF, the trial is noteworthy for its independent evaluation of a generic drug. “It’s very difficult to do a trial like this,” she said, “because you don’t have the financial support of a drug company.”

The study comes at a time of global concern about the price of the newer multiple sclerosis drugs, which can range from about $20,000 a year in Canada to about $70,000 a year in the United States, Oh said. One dozen drugs are now approved in many countries for RRMS, but there are few head-to-head studies to inform patients and physicians about the relative benefits and risks of each drug for optimal decision-making.

In further complications, none of the drugs have yet been shown to slow, halt, or reverse the progressive forms of MS. Many neurologists believe that earlier treatment offers more protection against the neurodegeneration and disability of progressive MS. Yet, it’s unclear which agents work best for which patients. In the absence of better evidence, it’s a matter of trial and error over several years to find an effective and tolerable compound for individuals with MS.

A modern look at azathioprine

Like many of his colleagues, Massacesi believes that treating MS early prevents the accumulation of debilitating damage that leads to worse outcomes. He adopted the philosophy in the early 1990s, when he began practicing in Italy. At that time, there were no drugs approved for MS, and AZA was a popular option in Europe.

“It was used the wrong way,” Massacesi told MSDF. Doctors concerned about long-term safety prescribed AZA when people were older and already disabled. “Now, everyone in MS knows that you treat before disability develops.”

In the mid-1990s, two safety studies showed that the cancer risk may increase slightly, but only after about 10 years on AZA and a cumulative dosing level (Amato et al., 1993; Confavreux et al., 1996). Similar long-term cancer risk studies of azathioprine in MS and other autoimmune diseases followed (Fraser et al., 2002; Taylor et al., 2004; Nero et al., 2004). This was good news to Massacesi, who had been prescribing AZA to young patients just after the second relapse then required for a confirmed MS diagnosis.

Almost no one noticed the AZA safety studies, he recalled to MSDF, because of the first exciting new RRMS clinical trial results for interferon β-1a. Soon, Massacesi was also recommending interferons. He noticed that his patients were not doing any better than those on AZA, which he has continued to prescribe.

Massacesi began to suspect that interferons were perceived as being more effective because the clinical trials with the newer drugs in the 1990s had been conducted with better methodology than that used in the 1980s with AZA. To test his idea, he organized an MRI study of people on AZA with a technique newly validated by the U.S. National Institutes of Health. AZA seemed to suppress new brain lesions just as well as in the interferon studies, he reported.

A new funding opportunity in Italy led to the new study. The Italian Medicines Agency, a counterpart to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, launched an independent research grants program in 2005, underwritten by royalties from the pharmaceutical industry, Massacesi told MSDF.

The noninferiority study of AZA against the β interferons started in 2008, involved more than two dozen MS centers across the country, and cost about $1 million. A comparable industry-funded study would have cost more than $30 million, Massacesi estimated. One budget bonus was that medicines used in the trial were charged to the national health service, thanks to a law passed especially to allow this cost-shifting in independent research studies of this kind. Massacesi coordinated the trial in collaboration with researchers at the Carlo Besta Neurological Institute in Milan.

The study was single-blinded, with the patients not being informed of the drug. Half were randomized to AZA, and half to interferons. The relapse evaluations were standardized with methods employed by other randomized trials at the time for the β interferons and glatiramer acetate.

Then came “something that almost ruined the study,” Massacesi said. During the recruitment, new McDonald diagnostic criteria for MS were published, allowing for an earlier diagnosis (Polman et al., 2011). The change was influenced by results of two randomized trials that found that interferon β was effective after a single relapse, Massacesi said. That meant that it was not ethical to hold treatment until a second relapse, as the AZA-interferon trial protocol dictated. Powered for 360 participants, the study was capped at 150. However, the independent data and safety oversight committee also recommended that the study continue at a recalculated lower power.

For Massacesi, the consistent results of the smaller trial at every measure reinforced his clinical experience that AZA was a reasonable alternative to interferon. “In 25 years, I’ve treated 400-500 people with these medications. I’ve seen many people who don’t tolerate interferon who tolerate AZA and vice versa. We know some people cannot tolerate AZA. They have a genetic resistance to the metabolites. They can be treated nicely with interferon.”

The findings have bigger implications for people without access to the newer drugs. “I see people from East Europe who come for a second opinion,” Massacesi said. “I can’t prescribe interferon. This could be a real revolution [in places such as] South Africa or the Middle East. People who can’t pay for interferon can be treated with the same percentage of success with this medication.”

Not inferior, not superior

For others, the study raises some cautions. “Noninferiority trials have to be scrutinized carefully because there are a lot of threats to the validity of a conclusion of a noninferiority trial,” said Gary Cutter, Ph.D., a clinical trial statistician at the University of Alabama.

Noninferiority trials were developed in the 1980s as a way to answer a clinical question about whether another medical intervention, such as a generic drug, can be used to achieve the same result, Cutter told MSDF: “Studies like this should be done, but in the right way with the right sample size and right inferiority margins.”

In one design difference, superiority studies start with a null hypothesis that both groups, on the drug or a placebo or comparative drug, are equally effective. The noninferiority trial takes the opposite starting position to disprove: The potential therapeutic is inferior to the known effective agents.

“Now the question becomes what do you mean by inferior,” Cutter told MSDF. The inferiority margin is a random choice, statistically speaking, he said. Some studies, including the one by Massacesi, have used the difference between the treatment effect and the placebo. A smaller study is more likely to have results showing that a treatment is similar when it is not, Cutter said.

In the AZA study, the smaller sample size does not necessarily make the findings incorrect, but it may limit the generalizability of the result, Cutter said. The study authors acknowledge a difficulty in explaining the rationale of randomizing patients between an old off-label generic and a new approved MS drug. Cutter praised the full disclosure in the paper of the intended and actual study size, as well as other limitations.

Several experts questioned the mixed group of interferons as a comparison, because of the differences in effectiveness and the different benefit-risk ratios (Filippini et al., 2013) among the three drugs. In a comment at PLOS ONE, Alexis Clapin, who worked for Merck Serono, wrote, “Comparing interferons beta as a whole to another product is misleading for patients. Such studies are pushing patients to second line products with their increased risks.”

In the paper, Massacesi and his colleague explained that they grouped the interferons to avoid perception of a conflict of interest. A sensitivity test excluding Avonex, which may be less effective (Filippini et al., 2013), showed results similar to those of the larger study, he said.

Even with the new evidence, physicians may find AZA a higher-maintenance drug to prescribe, Massacesi speculated. It requires closer clinical monitoring during the first year to titrate the dose to the lymphocyte count, manage the early gastrointestinal issues, and monitor for the small percentage of patients who cannot tolerate the drug due to genetic variations. But for some patients, AZA provides a higher quality of life without the flulike symptoms of interferons and with a better side effect profile than the new drugs, he said.

For Massacesi, another bonus of azathioprine is knowing quickly whether a person will tolerate the medication, to make the best early treatment decision. In the study, doses of the interferons were titrated for the first 4 weeks, while it took up to 8 weeks to bring the azathioprine doses to full strength for each patient.

How will the findings change day-to-day practice? Massacesi continues to regard AZA as an optimal first-line therapy that may offer better outcomes than interferons. Oh thinks the study shows AZA is “a great option,” but would not be a treatment of choice except “when there are no other alternatives.”

Key open questions

- How does azathioprine compare with β interferons using disability as a longer term endpoint? What trial designs are feasible?

- Is the noninferiority design a less expensive way to test repurposed drugs in MS against known effective agents?

- What are the appropriate clinical questions and drugs in MS for noninferiority designs? And what are the goals: to save money or to obtain efficacy with reduced risk?

Disclosures and sources of funding

The present study was funded by AIFA (Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco, www.agenziafarmaco.gov.it). Dr. Solari was a board member for Novartis, Biogen Idec, and Merck Serono, and has received speaker honoraria from Sanofi-Aventis. Dr. Massacesi has received reimbursements for meeting participation or educational grants from Biogen Idec, Merck Serono, Sanofi-Aventis, and Novartis. In addition, he is a member of the Scientific Advisory Group on Neurology of the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and of the Italian Medicines Agency (Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco, AIFA) Advisory Committee on Neurology, but the opinions included in this paper do not involve this activity. Dr. Tedeschi has received reimbursements for meeting participation or educational grants from Biogen Idec, Merck Serono, Sanofi-Aventis, and Novartis. In addition, he was a member of the Italian Medicines Agency (Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco, AIFA) Advisory Committee on Neurology, but the opinions included in this paper do not involve this activity. All the other authors have declared that no competing interests exist.