PPMS vs. RRMS: A Distinction Without a Difference?

A study using ultrahigh-field MRI found identical brain lesions in primary progressive and relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis

The relationship between primary progressive multiple sclerosis (PPMS) and relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS) continues to vex researchers. A new ultrahigh-field magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) study has revealed that brain lesions are alike in these two forms of MS (Kuchling et al., 2014). Although scientists don’t expect the paper to settle the debate about PPMS and RRMS, it does strengthen the suggestion that PPMS, which is currently considered untreatable, may respond to drugs that inhibit relapses in RRMS.

From a patient’s point of view, PPMS and RRMS differ dramatically (see “Altered Immunity, Crippled Neurons”). The severity of RRMS waxes and wanes, as symptomatic periods alternate with stretches in which the illness appears to fade or even disappear. In contrast, people with PPMS, who account for about 15% of cases, can expect their condition to continually deteriorate. More than half of the time, RRMS eventually transforms into secondary progressive MS, which resembles PPMS in that patients’ neurological function relentlessly declines.

PPMS and RRMS also diverge in their demographics and response to drugs. When RRMS patients are diagnosed, they are usually in their 20s or 30s, whereas PPMS patients are around 10 years older. Although RRMS is two to three times more common among women than among men, the gender ratio for PPMS is close to 50:50. When researchers have tested anti-inflammatory and immune-modulating drugs that are beneficial for RRMS, such as interferon β and rituximab, they’ve detected little effect on PPMS (Comi, 2013).

Despite these disparities, in some ways PPMS and RRMS are indistinguishable. For example, studies have reported that they overlap in characteristics such as the amount of demyelination and remyelination, the number of cortical lesions, and the extent of acute axon damage (Antel et al., 2012). And so far, researchers haven’t been able to pinpoint any imaging finding or pathological change that distinguishes PPMS from RRMS, Anthony Traboulsee, M.D., told MSDF. “Under the microscope or in MRI, they look the same,” said Traboulsee, who is the MS Society of Canada Research Chair at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver and was not involved with the new study. The convergence between the two MS forms also extends to gene expression patterns (Ratzer et al., 2013) and the identities of susceptibility genes (Cree, 2014).

Researchers are still debating how to interpret these similarities and differences and nail down the relationship between RRMS and PPMS. Emphasizing the contrasts, a few scientists go so far as to propose that PPMS and RRMS are separate illnesses with unique causes. At the opposite end of the spectrum is the contention that PPMS and RRMS are two stages of the same disease. According to this hypothesis, PPMS patients have already undergone a nearly silent version of RRMS. They may have had an episode of MS symptoms, but they never had the relapse that would have led to a diagnosis.

The middle ground on PPMS and RRMS, Traboulsee said, is that “most people feel they are both MS, but they are distinct because their clinical behavior is different.” The view that PPMS and RRMS are unequal but not separate has affected research into treatments, he noted: PPMS patients have been excluded from most clinical trials.

Zooming in

One possible explanation for the lack of consistent MRI differences between PPMS and RRMS is that researchers couldn’t look closely enough. The 1.5-tesla and 3-T MRI scanners used in hospitals and most studies can’t reveal as much detail as ultrahigh-field 7-T MRI scanners, which are available at only a few institutions around the world, co-author Friedemann Paul, M.D., told MSDF. He is principal investigator in the Department of Neuroimmunology at the NeuroCure Clinical Research Center, Charité-Universitaetsmedizin Berlin in Germany. So far, 7-T MRI has proven its ability to discriminate RRMS from conditions that can be confused with MS, such as symptomless white matter lesions and Susac syndrome (Tallantyre et al., 2011; Wuerfel et al., 2012). Paul and colleagues decided to take advantage of this more discerning type of MRI to compare RRMS and PPMS patients.

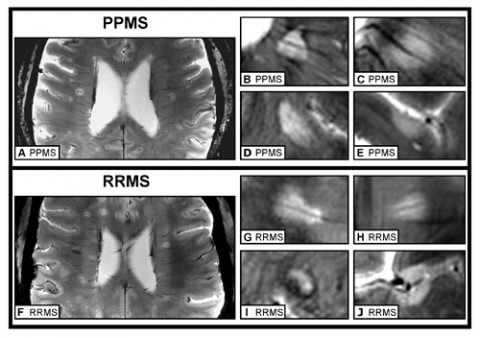

The team scanned the brains of nine people diagnosed with each MS variety, all of whom were between their mid-30s and their mid-50s. The researchers tallied and measured lesions in the white and gray matter, both of which accrue damage in MS (Pirko et al., 2007). “What we found was that the patients were more or less equal,” Paul said. Whether they had PPMS or RRMS, subjects were equivalent in the number, shape, location, and distribution of their lesions. Only one measurement varied between the groups: RRMS patients tended to have larger lesions, confirming what previous studies had found. The team reported its findings in the journal Multiple Sclerosis.

Lesions from both groups were also comparable in their subtle structure. They showed a so-called central vein running through the middle and a dark band along the edge, known as a hypointense rim. These two characteristics might be diagnostic for MS, the authors concluded. The team also suggested that the central vein, which doesn’t show up in studies that use less powerful MRI scanners, indicates that inflammation around blood vessels is important in the pathology of RRMS and PPMS.

The 7-T scanner also displayed its discriminating power by allowing the team to visualize subpial lesions in the cortex. These lesions are characteristic of MS, but they are not visible at 1.5 T and are only barely visible at 3 T, Paul said. The researchers were able to show that the lesions were equally abundant in PPMS and RRMS patients, and future studies may be able to clarify their clinical significance.

“We have strong evidence from our study that PPMS and RRMS belong to the same disease spectrum,” Paul said. But the researchers acknowledge several limitations of their work. The sample size was small, primarily because subjects are hard to find, Paul said. A 7-T MRI scanner generates such a powerful magnetic field that people who have pacemakers or joint implants can’t participate. That restriction makes it particularly difficult to recruit PPMS patients, who tend to be older and are more likely to have these devices, Paul added. Another limitation, he noted, is that the team didn’t image the spinal cord, which is challenging to visualize with 7-T MRI. Lesions there disable PPMS patients, and it’s possible that the PPMS and RRMS subjects would exhibit differences, he said.

“The strength [of this study] is the high tesla,” Tanja Kuhlmann, M.D., associate professor for neuropathology in the Institute of Neuropathology, University Hospital Münster in Germany, told MSDF. Using the more powerful scanner, “they have actually confirmed what had been found in other studies” about the similarity between PPMS and RRMS, said Kuhlmann, who wasn’t involved in the work.

Traboulsee agreed. The results “reinforce the general finding that a pathologist cannot tell which patient has RRMS,” he said. However, he added, the small sample size means the study won’t quell the controversy about the relationship between RRMS and PPMS.

Scanning the horizon

By highlighting the overlap between the two MS forms, the findings offer some hope to patients, Traboulsee said. The FDA has not approved any treatments for PPMS, but 10 drugs that curb RRMS relapses have reached the clinic. Although several of these drugs have fared poorly in PPMS clinical trials, researchers haven’t determined whether others such as fingolimod and natalizumab work against PPMS. “We are now in a position to ask whether we can affect progression with these very effective treatments,” Traboulsee said.

The paper doesn’t solve the biggest mystery: If RRMS and PPMS are so similar, why are their clinical courses disparate? “At the moment we don’t have an explanation for why patients behave so differently,” Kuhlmann said. Paul noted that 7-T MRI might provide some insights by allowing researchers to address issues such as whether the distribution of lesions affects the clinical presentation of the illness and whether lesions change over time. Further evidence of the resemblance between RRMS and PPMS emphasizes the importance of discovering why MS patients progress. “With RRMS, all of these patients are at risk of becoming progressive,” Traboulsee said.

Key open questions

- Why do PPMS patients have smaller lesions, and does their size affect the course of the illness?

- Which treatments, if any, will halt or slow the progression of PPMS?

- Would a larger MRI study uncover subtle differences between RRMS and PPMS patients?

- Do subpial lesions have an effect on MS progression?

Disclosures and sources of funding

The study was funded by the German Research Foundation. Friedemann Paul has received speaker honoraria, travel grants, and research grants from Teva, Sanofi, Bayer, Merck Serono, Biogen Idec, and Novartis. He is supported by the German Research Foundation and the German ministry of education and research, and he has received travel reimbursement from the Guthy Jackson Charitable Foundation. Other co-authors have received grants, consulting or speaking honoraria, travel grants, and lecture or research fees from Novartis, Merck Serono, Bayer, Teva, Genzyme, and Biogen Idec. Co-author Lutz Harms serves on the advisory boards for Biogen Idec, Genzyme, and Novartis; co-author Jens Wuerfel serves on the advisory board for Novartis. Co-author Berit Rosche has participated in meetings sponsored by Bayer Healthcare, Merck Serono, Biogen Idec, Novartis, Ovamed, and Teva Pharmaceuticals. Co-author Thoralt Niendorf is founder of MRI.TOOLS GmbH.

Anthony Traboulsee has received grant funding from the MS Society of Canada, the Canadian Institute for Health Research, the Lotte and John Hecht Foundation, the Vancouver Hospital Foundation, Bayer, Roche, and Biogen. He has served on a data safety monitoring board for Merck Serono and a clinical trial steering committee for Roche. He received honoraria or travel grants from Biogen, Teva Canada Innovation, Roche, Merck/EMD Serono, and Chugai Pharmaceuticals.

Tanja Kuhlmann has received honoraria from Novartis, Sanofi-Aventis, Bayer-Schering, Merck Serono, and Teva.