Gate Crashers

Vascular barriers and multiple sclerosis

Ask most neurologists what part of the body breaks down in multiple sclerosis and they’ll say “myelin.” But before the disease can erode these casings that shield axons, it must wear down another piece of the body’s armor: the blood-brain barrier. This structure normally defends the central nervous system from potentially harmful components in the bloodstream, including those that could cause inflammatory damage. In MS, however, the protective properties of the BBB weaken, and immune cells attack with a myelin-degrading fury.

No one has identified the key triggers of MS, but whatever prompts the disease, it causes immune cells to wreak havoc on myelin, and conventional wisdom holds that this assault plays a central role in the disease. Although researchers are increasingly realizing that many types of cells contribute to this devastating inflammation, much research on the BBB has focused on T cells. The body normally weeds out T cells that recognize its own proteins. The system is not foolproof, however, and some potentially self-reactive T cells escape destruction. If such errant immune cadets subsequently encounter bits of a person’s normal proteins in the wrong context—in association with particular molecules on so-called antigen-presenting cells—they can raise a ruckus. In MS, myelin- or other peptide-presenting cells rouse such self-destructive T cells into action and set in motion a series of events that disrupts the BBB.

How this process unfolds is not yet clear. The cascade could begin outside the CNS, and the stimulated T cell could then make its way through the BBB, or a T cell that is surveying the CNS for intruders might get stirred up and spark trouble.

Regardless of how T cells start to go awry, at some point these immune cells and others storm the CNS through a weakened BBB. "When you talk about T cells getting into the CNS, you're talking about two different things," says Richard Ransohoff, a neurologist at the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio (and an MSDF scientific adviser): the step at which a few pilot immune cells—those that have been revved up by antigen-presenting cells—weaken the BBB and the later step at which throngs of immune cells cross that compromised barrier.

Therapies that reduce immune cell traffic into the CNS, such as natalizumab (Tysabri), reduce relapses and delay disability in some MS patients. However, the medication can make patients susceptible to a life-threatening viral infection of the brain. This observation underscores the necessity for the immune system to fight microbes even in the body's barricaded control tower. But the pathways by which its components access the CNS to combat invaders might act as conduits of destruction in MS. To find ways to limit the harmful influx while allowing healthy surveillance of menacing microbes, researchers are asking how and where immune cells leave the bloodstream and make their way into the CNS. Some scientists are studying how the BBB forms during fetal development to harness this process and bolster or even repair the structure in adulthood; others are probing how the BBB is damaged in MS with an eye toward thwarting destructive activities. If we can understand how and why the BBB is broken down in this illness, we might be able to prevent immune cells from inappropriately entering the CNS and so stop disease activity, says Richard Daneman, a molecular biologist at the University of California, San Francisco.

As the site of damage commonly used to identify new lesions in MS (see “More Than Meets the Eye”), the BBB is traditionally thought to be the gate through which the majority of pathogenic immune cells cross. However, the BBB, which barricades narrow blood vessels such as capillaries within the brain tissue, isn't the only place to look. The brain has other entry points, including some nearly unguarded back doors, which could play a significant role in the disease as well. Studies published in the past few years suggest that alternative entrances might allow the pioneering immune cells of MS to infiltrate the brain and instigate an immune cascade that leads to the inflammatory activity that characterizes the disease.

Safeguarding the brain

In most regions of the body, blood vessels are "leaky" and allow molecules, ions, and cells to flow into muscles, skin, and other tissues. The BBB, however, protects the delicate brain from potentially harmful material. Instead of the porous blood vessel walls that separate the bloodstream’s contents from most of the body’s tissues, unique cellular and molecular structures form a biological mortar between the blood and the CNS.

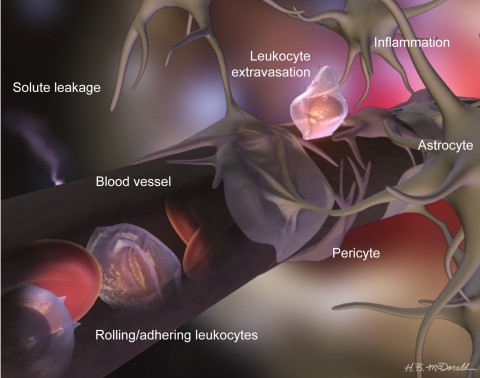

In the walls of capillaries and certain other narrow vessels of the CNS, clusters of sticky molecules form so-called tight junctions, which glue together adjacent endothelial cells. Only small and lipid-soluble molecules can pass through these cellular seams; others must enter the healthy CNS through specialized transport systems. Two additional cell types strengthen the vessel walls: pericytes, which support and closely wrap around the endothelial cells, and astrocytes, star-shaped brain cells that send out projections that enclose much of the blood-vessel perimeter.

The components of the BBB work together to create the barrier, Daneman says, yet they can be disrupted independently. Loss or improper localization of tight-junction proteins, reorganization of fused membranes, and perturbation of production or activity of other proteins can make the barrier permeable to experimentally injected dyes and, more importantly, to immune cells and other blood-borne components. Each cellular member of the BBB guard also plays an important role. In 2010, Daneman and his colleagues reported that pericyte-lacking mice have a leaky barrier, suggesting that these support cells normally help establish and maintain the protective structure (Daneman et al., 2010). In the absence of pericytes, the researchers found, CNS endothelial cells turn on genes that are normally active in endothelial cells of leaky peripheral blood vessels. These observations suggest that pericytes normally suppress the production of molecules that allow bloodstream components to pass. For instance, endothelial cells in the brains of mice without pericytes manufacture unusually large amounts of adhesion molecules that grab leukocytes—white blood cells, such as T cells and macrophages—and help the immune cells cross the BBB. Some of these sticky molecules are also overproduced in CNS blood vessels of MS patients, where they presumably help leukocytes migrate from the bloodstream into brain tissue. How these results translate to patients is not yet clear, but Daneman has some ideas. "If … pericytes [normally] stop leukocyte entry, then a very key step in MS may be a loss of pericyte-endothelial cell interaction," he says.

Astrocytes also promote formation of the BBB. In November 2011, Alexandre Prat, a neuroimmunologist at the University of Montreal in Canada, and colleagues found that astrocytes and BBB endothelial cells communicate through Hedgehog signaling, a pathway that contributes to many physiological processes, including cell maturation and tissue repair, to promote a tight and restrictive barrier (Alvarez et al., 2011). Stifling the Hedgehog signaling pathway in mice caused the BBB to leak.

Opening the gate

Although the BBB largely blockades the brain from the rest of the body in healthy individuals, it allows some immune cells to enter so they can survey the CNS for pathogens and other toxins. Leukocytes are thought to cross the BBB most readily at post-capillary venules, the small vessels that collect deoxygenated blood from capillaries, the vasculature's finest branches. At the venules, through a series of steps, the immune cells traverse the endothelial wall and enter the brain.

Leukocytes in the bloodstream roll along the vascular wall by repeatedly grabbing and releasing molecules on the vessel’s surface. In inflammatory disease states—when microbes threaten or when autoreactive immune cells have been stimulated—immune cells in the CNS produce molecules called cytokines that goad endothelial cells to generate such adhesive molecules. Endothelial cells then grab hold of the rolling leukocytes, which subsequently cross the BBB. “The endothelial cell coordinates the entry of immune cells into the brain,” says Jonathan Steven Alexander, a cardiovascular biologist at Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center in Shreveport, Louisiana. “It's basically saying, 'Stop here, something is going on, please investigate.' "

Hedgehog signaling might keep this process in check, Prat says. When that signaling pathway is inhibited, his team showed, more T cells invade the brains of mice with a disease that mimics aspects of MS—experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE)—and increase demyelination.

Conversely, stimulating Hedgehog signaling in a sheet of human BBB endothelial cells grown in culture causes fewer inflammatory T cells to stick to and migrate across the cellular layer. Cell culture studies and samples from the brains of deceased MS patients suggest that inflammation activates the Hedgehog pathway, perhaps reflecting an attempt to stem the influx. Within the demyelinating lesions of these patients, astrocytes, endothelial cells, and leukocytes all contain more Hedgehog signaling components than do similar cells in healthy tissue. Given the likely immune-quieting role of the pathway in a healthy body, its activity might bring about the recovery period that follows the cyclical inflammatory attacks that affect most MS patients, Prat says. In a given lesion, the BBB does not remain open forever—only a few weeks on average—and Hedgehog signaling might help repair each breach.

In the textbook model of invasion, immune cells cross into the CNS by passing between the endothelial cells that compose the BBB. Using microscopy, however, Britta Engelhardt, a neuroimmunologist at the University of Bern, and her colleagues have observed immune cells making their way through endothelial cells in brain tissue taken from mice with EAE. “They drill a little tunnel there," Engelhardt says, and leave the endothelial cell junctions intact through an unknown mechanism.

In a November 2011 study, her team showed that shoring up the BBB's bonds with an additional tight-junction protein does not reduce inflammation in the EAE mouse brain (Pfeiffer et al., 2011). This observation suggests that immune cells can indeed cross the barrier without going through cell junctions; rather, they can pass through the cell bodies. It’s not clear which of the two pathways is more common, she says, nor whether endothelial cell signaling guides the process or whether different types of immune cells take different routes.

The extra sealant in the tight junction, however, eases the severity of EAE symptoms and limits the amount of small blood-borne factors, such as injected dyes and a normal component of plasma, that cross the BBB. This result suggests that contents of the blood other than immune cells contribute to MS-like pathology, she says.

Inflammation in the CNS also causes immune cells within the brain and endothelial cells to increase production of BBB-disrupting enzymes called matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs). Normal MMP activity helps maintain a healthy BBB structure by clearing away degraded materials, but an excess of MMPs, which gnaw at the restrictive junctions between endothelial cells as well as structures that support astrocyte projections, can cause trouble. Elevated levels of some MMPs—seen in MS patients and rodents with EAE—are linked to loss of barrier strength, increased leukocyte access to the brain, and ultimately, demyelination, Alexander says: "We want to find out … which MMPs are the important ones that are activated and contribute to blood-brain barrier disturbances in MS."

The back staircase

T cells that cross the endothelial barrier as part of an inflammatory response must overcome at least one more challenge before they can roam the CNS and damage axons. A protein called CXCL12 that dwells on the tissue—or abluminal—side of the blood vessel can catch T cells and hold them there. The protein “acts in some ways like a filter," says Robyn Klein, an infectious disease physician and neuroimmunologist at Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri. "It actually prevents leukocytes from entering the brain tissue.” Instead, most of them are stuck on the vessel.

Leukocytes can interact with other cells in the space just outside the blood vessel, but in general, they can’t let go until CXCL12 is removed from the brain-facing surface of endothelial cells. A protein called CXCR7 at the surface of those endothelial cells helps set leukocytes free. It binds CXCL12 and then shuttles CXCL12 to a garbage disposal–like organelle, the lysosome, inside the cell's cytoplasm. The amount of CXCR7 at post-capillary venules increases in EAE-afflicted rodents relative to healthy animals, Klein discovered. With less CXCL12 at the surface of endothelial cells, more leukocytes can move away from the blood vessel wall and into the brain tissue. Comparison of autopsy material from MS patients with samples from patients with other neuroinflammatory diseases suggests that "this process of internalization of CXCL12 seems to be specific for MS," Klein says (McCandless et al., 2008).

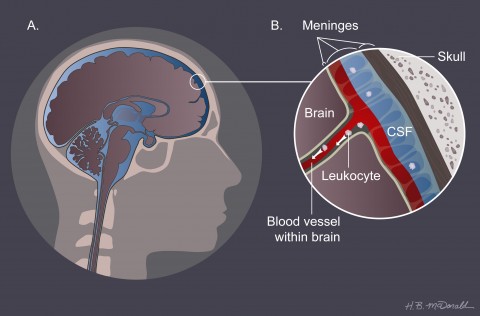

In February 2011, Klein and colleagues reported that a chemical inhibitor that renders CXCR7 unable to ferry CXCL12 to the lysosome blocks immune cells in EAE mice from entering the brain and spares the animals from paralysis (Cruz-Orengo et al., 2011). In addition to finding early evidence that CXCR7 might be helpful as an MS treatment, this study uncovered a second possible route by which immune cells make their way into the brain. Instead of accumulating at the BBB, leukocytes in the treated animals piled up on blood vessels within the meninges, a set of three protective layers that surround the brain and hold the cerebrospinal fluid that cushions the organ. The observation that they amass here rather than at the BBB in the brain suggests that the meninges could sometimes serve as the site of first entry, Klein says.

In MS, Klein speculates, myelin-activated cells cross through or between the endothelial cells of the blood vessels in the meninges and then crawl down along the external surface of the vessels into the brain, probably by interacting with CXCL12. "We are just starting to understand how the behavior of the vascular system really participates in this process," Klein says. Her data and that of others suggest an important role for the meninges in the early steps of disease, she says. For example, Alexander Flügel, a neuroimmunologist at the Max Planck Institute for Neurobiology in Munich, Germany, used a high-resolution fluorescent microscopy technique to watch the first pathogenic cells migrating into the CNS through the meninges in mice with EAE (Bartholomaus et al., 2009). Nonetheless, other studies point to leukocytes crossing at the BBB. The relative importance of each migration point is unknown; "it's an ongoing debate," Klein says.

The debate applies to humans as well as to mouse models. In theory, scientists would like to trace the path of MS-promoting immune cells from the thymus, where T cells mature, to the brain so that they can identify when and where the self-destructive pathology of MS begins. But that task is difficult to achieve in MS patients because by the time symptoms arise, the cells have already completed their initial foray into the brain. Although no strategy currently exists for probing the very first steps of disease in humans, Ransohoff and colleagues have been exploring relatively early stages using patient biopsies.

Conventional MRI imaging of MS reveals lesions in the brain’s white matter, but it often misses lesions in the gray matter. Ransohoff took advantage of a large collection of MS biopsies at the Mayo Clinic. In 20% of the samples that contained tissue (but tiny amounts of it) from the cortex, the outer gray-matter layer of the brain, he and his colleagues found demyelination that could not be associated with a white-matter lesion (Lucchinetti et al., 2011)—a “huge fraction,” he says, given how little gray matter existed in each sample. This gray matter lies just below the meninges. The loss of myelin provides circumstantial evidence that immune cells gain initial access to the CNS from the meninges, as it stands to reason, Ransohoff says, that the damage would occur earliest close to where the first immune cells cross into the CNS. “That supports our idea that lesions might be related to meningeal inflammation." The result, he says, adds weight to consideration of a meningeal route for the disease-causing T cells of MS.

Monitoring trouble

Whichever route cells take to enter the CNS, eventually inflammation in the brain leads to a weakened BBB. Permeability of the BBB is so central to MS that it takes center stage in monitoring disease activity (see “More Than Meets the Eye”). When the BBB breaks down, fluids leak into the brain, which can be seen in specialized MRI scans. Typically, a small-molecule dye called gadolinium (Gd) is injected into patients and flows through the cracks of the BBB, highlighting these spots on the image. MRI scans are currently an integral part of patient care, but scientists are on the hunt for molecular markers of BBB disruption that could provide faster and cheaper ways to diagnose MS and monitor therapeutic outcomes.

Microparticles, small packets of plasma membrane and intracellular fluid found in the bloodstream, show promise as such a biomarker. When CNS endothelial cells are exposed to inflammatory cytokines, the stressed cells shed these bits, which activate immune cells called monocytes. Alexander and colleagues have found unusually large amounts of these substances in the blood of MS patients, and concentrations of microparticles correlate with the number of Gd-enhanced lesions detected by MRI. Perhaps the BBB is losing pieces of the endothelial membrane, Alexander says, which “may contribute to a compromised blood-brain barrier.” Blood-borne cell fragments called platelets also cast off microparticles when they promote binding between leukocytes and endothelial cells. To lay the groundwork for a simple blood test that would provide a way to objectively measure disease severity, Alexander and Louisiana State University's Alireza Minagar are currently relating the amount of microparticles in the blood of patients to their MS-related disability and analyzing the effects of therapy on quantities of these biomarkers.

Bracing the gate

By the time patients visit their doctor with symptoms of MS, the disease has already progressed past the point of initial entry of immune cells into the CNS. However, therapeutics to prevent future immune cell entry could still be useful. "Relapses will come," Flügel says, and bring with them new waves of inflammatory cells that can cross a weakened BBB. As the scientific community's understanding of the development, maintenance, function, and breakdown of the blood-CNS barriers grows, so do opportunities for finding new treatment methods. Such endeavors, however, must be carefully undertaken.

Although the pathology of MS requires immune cells to flood the brain through a broken BBB, imagined therapeutics that would cement the structure shut would not provide a panacea. Versions of that idea have been tested with drugs that inhibit leukocyte-endothelial cell interactions, with mixed results. Recall that natalizumab, for instance, restricts immune cells' abilities to cross the endothelial barrier. The drug does significantly reduce attacks in patients with relapsing-remitting MS, but it increases the risk of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML), an often deadly viral brain infection for which there is no cure.

"What we've learned from the Tysabri story and PML is that immune surveillance is important," Klein says. "If you block immune surveillance, then you can increase the risk of severe infections of the CNS." Flügel suggests that tweaking the permeability of the BBB might open a feasible therapeutic avenue. "The more we can learn about how much we can block the blood-brain barrier and what molecules are involved, the better equipped we will be to allow physiologic immune surveillance but prevent activated pathogenic immune cells from entering the brain," he says.

Studies on the molecular activities of inflamed BBB point to specific molecules to target. For example, some of Alexander’s and Minagar's studies on MMPs’ role in MS pathology suggest that restraining these enzymes could be useful in the clinic (Minagar et al., 2008). They found that doxycycline, a drug that functions as an antibiotic and an inhibitor of MMP activity, improved the treatment of MS when combined with interferon β-1a, a drug commonly prescribed as an anti-inflammatory for MS patients. "The addition of MMP inhibitors to treatment of MS might improve the overall outcome in MS by maintaining a stable blood-brain barrier," Alexander says. Knocking out one class of enzymes is less risky than blocking CNS access for an entire class of cells, he says, as Tysabri does. Yet he is cautious about MMP inhibitors as a drug. "Some of our studies have shown that MMPs like MMP-9 may sometimes have beneficial roles in the brain," Alexander says. Mice that lack MMP-9 are more susceptible to brain hemorrhaging, for example, so MMP-inhibitor treatment might not be suitable for all patients.

The increasing evidence for immune cell activity in the meninges as an early step in MS could have important implications for therapy development. "If all you are looking at is crossing the BBB that’s already inflamed, whereas the whole process starts because cells [are] getting into the spinal fluid, … you may be missing the boat," Ransohoff says. Furthermore, the meninges might be a preferred spot for studying the effects of therapeutic agents in rodents because microscopic techniques that can't be used to look deeply enough into the brain to see the BBB can still allow scientists to visualize details of live cellular activity in the meninges. "I think we can learn how established or newly developed therapeutics influence [immune cell behavior in the meninges]" with these tools, Flügel says. Such progress would allow researchers to better test and develop new treatments that interfere with entry into the CNS through this route, he adds.

"We clearly know that demyelination is an important and essential characteristic of the disease," Alexander says. "But how do we get there?" Progress in understanding exactly how the BBB bulwark breaks down will help scientists devise ways to foil the process. These efforts might one day help forge armor that can fend off the earliest steps of nerve-cell damage.

Key open questions

- Could an inherently faulty BBB play a role in MS, and if so, what are the physiological differences (e.g., gene expression, protein expression, cellular organization) of the undisturbed BBB between people with and without MS?

- Are the different forms of MS, such as relapsing-remitting and progressive disease, associated with different abnormalities of the cellular components of the BBB (endothelial cells, pericytes, and astrocytes)?

- What are the molecular mechanisms that lead to BBB disruption in MS? Are these same mechanisms found in other diseases or conditions (such as stroke) that feature BBB disruption?

- In addition to T cells, other leukocytes such as B cells and macrophages play a role in the course of MS. Do each of these different cells have a preferred route into the brain, such as through the BBB or into the meninges?

- Similarly, which T cell subtypes (e.g., CD4+, CD8, etc.) enter the meninges, and what is their behavior inside these protective layers?

Image Credits

Thumbnail on landing page, Fig.1 and Fig. 2. Courtesy of Heather McDonald.