MS Patients Positive for Oligoclonal Bands Have Greater Brain Atrophy

A new global brain MRI study shows that patients who test positive for oligoclonal bands have greater loss of white matter than MS patients lacking those bands. The results of the study suggest that there may be reason to consider MS patients without oligoclonal bands to be a clinically distinct subgroup.

Patients lacking oligoclonal bands (OCBs) have less overall brain atrophy than those who test positive for the bands, according to a new study published in the Journal of Neuroimmunology. The authors argue that OCB-negative patients should be considered a distinct subgroup of MS patients (Ferreira et al., 2014).

Oligoclonal bands are immunoglobulins that collect in a patient’s blood plasma or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). The presence of OCBs in the CSF has often been used as a diagnostic criterion in MS. Though not every person with MS has OCBs, their presence is generally associated with a younger age of onset and a poorer disease outcome. According to the authors of the new study, most MRI studies of OCB-positive and -negative patients have focused only on the differences between brain lesions. Theirs, they say, is the first study to look at global CNS differences between these two subsets.

The study

The researchers performed MRI scans on 28 OCB-negative and 35 OCB-positive patients with either relapsing-remitting MS or secondary progressive MS and matched them for disease activity. Overall, the OCB-positive patients had greater brain atrophy than the negatives, particularly in white matter areas (p = 0.029).

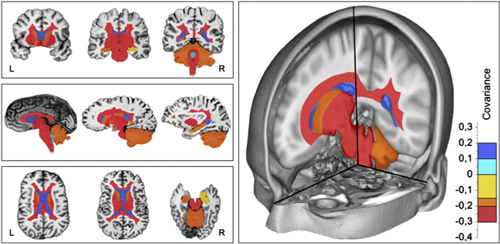

From there, the team looked at regions of the brain, using three different multivariate orthogonal projections to latent structures (OPLS) statistical models. Variables included age, gender, MRI protocol, disease course, age of onset, disease duration, treatment duration, and Expanded Disability Status Scale scores. The first two OPLS models looked at cortical and juxtacortical regions. The third OPLS model looked at subcortical structures (basal ganglia; diencephalon; hippocampus; amygdala; cerebellum; the corpus callosum; lateral, third, and fourth ventricles; and the periventricular and deep white matter).

The third model was the only one that reached statistical significance. In general, the researchers found that OCB-positive patients had the same amount of gray matter as OCB-negative patients, but that the positives had less white matter and greater CSF volume. At the regional level, the OCB-positive patients had less volume in the basal ganglia, diencephalon, cerebellum and hippocampus. In regional white matter areas, OCB-positive patients had greater volume loss in the corpus callosum, the periventricular-deep white matter, the brainstem, and the cerebellum white matter.

One possibility that could explain the difference, according to the researchers, is epitope expression. Perhaps OCB-negative patients have a different epitope expression than OCB-positive patients, arising from a different expression of HLA class II genes. They suggest that this difference would mean that OCB-negative patients represent a different subgroup of MS than OCB-positive patients. Of course, researchers could only confirm that with further studies with larger sample sizes.

If OCB-negative MS patients do belong in a distinct subgroup, that would have implications for treatment. The authors suggest that it’s possible that OCB-negative patients might have a different disease progression and different responses to DMTs, but no one has noticed this difference so far. It’s possible that the classification would also be relevant to the inclusion of OCB-negative patients in clinical trials.

Key open questions

- How should the characterization of OCB-negatives versus -positives be pursued further?

- If OCB-negative patients are indeed a subgroup of MS, how should that be included in the diagnostic criteria for all forms of MS?

Disclosures and sources of funding

Ferreira and his team received support from the Strategic Research Programme in Neuroscience at Karolinska Institutet, the Swedish Brain Power, the regional agreement on medical training in clinical research (ALF) between Stockholm County Council and Karolinska Institutet, the Erik and Edith Fernström Foundation for Medical Research, the Swedish Society of Medicine, and the Fundación Canaria Dr. Manuel Morales. They claim no competing interests.

Comments

The fact that multiple sclerosis (MS) has a heterogeneous course has led investigators to assume that MS could be considered as a syndrome and, therefore, separate disease entities may be identified. So far, the only successful example is the identification of neuromyelitis optica as pathogenetically distinct from MS. We argue that the subgroup of approximately 5% to 10% of MS patients lacking the typical oligoclonal immunoglobulin G bands in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) (OCB-negative MS) would be a strong candidate to be the next disease to emerge out of the MS complex.

Several preliminary reports establish that OCB-negative MS is immunogenetically distinct from typical MS patients carrying such bands (Mero et al., 2013). In addition, OCB-positive patients are reported to have lower age of onset and a more unfavorable outcome, i.e., evidence indicates a different course (Imrell et al., 2009). In the study reported here, we observed that OCB-negative MS patients showed less evidence for global and regional brain atrophy.

It remains possible that OCB-negative MS is in itself a pathogenetically heterogeneous group of MS phenocopies. However, the now-confirmed association of OCB-negative MS with alleles of HLA-DRB1*04 indicates a specific immune response trait early in disease arguing for at least some uniformity of the subgroup (Mero et al., 2013).

In summary, our observations, if supported by future reports, could lay the foundation for OCB-negative MS as a separate disease entity and should prompt efforts to identify unique pathogenetic mechanisms and in consequence specific treatment efforts.

References:

Imrell K, Greiner E, Hillert J, Masterman T. HLA-DRB115 and cerebrospinal-fluid-specific oligoclonal immunoglobulin G bands lower age at attainment of important disease milestones in multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimmunol 2009, 210(1-2):128-130.

Mero IL, Gustavsen MW, Saether HS, Flam ST, Berg-Hansen P, Sondergaard HB, Jensen PE, et al. Oligoclonal band status in Scandinavian multiple sclerosis patients is associated with specific genetic risk alleles. PLoS One 2013, 8(3):e58352.

Sincerely,

Jan Hillert, Daniel Ferreira, Eric Westman, and Virginija Danylaité Karrenbauer

Intriguing study particularly since WM atrophy is tied to local IgG synthesis and unlikely to explain why axonal loss, a hallmark of atrophy is restriced to WM in OCB positive patients. It has been shown in small sample-sized studies that OCB banding is higher in African Americans (AAs) compared to Caucasians and it is plausible that aggressive B suppression in AAs might be required as part of treatment regimen.

One could surmise that WM atrophy in AAs is also possibly greater than found in Caucasians given similar EDSS scores, disease duration and age/sex variables.

It is perhaps time to a) perform CSF analysis in ALL MS patients, and b) to treat those with more OCBs (as an example, > 8) aggressively and selectively with B cell suppressive therapy. There ought to be an algorithm based on B cell reactivity and type of therapy to be initiated.

Jagannadha Avasarala, MD, PhD