Stopping Natalizumab May Increase Risk of MS Relapse

The RESTORE trial showed that MRI and clinical MS activity recurred during natalizumab interruption in some patients who had been relapse-free for 1 year

Despite use of other therapies, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and clinical activity of multiple sclerosis (MS) recurred during natalizumab interruption in some patients who had been relapse-free for 1 year, according to a randomized trial published online ahead of print on March 28 in Neurology (Fox et al., 2014).

Natalizumab (Tysabri, Biogen Idec) is known to be effective in treating MS, but increased duration of treatment is associated with increased risk of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) among patients who are anti–JC virus antibody–positive. In theory, planned interruption of natalizumab therapy might lessen PML risk, but no prospective controlled studies have previously examined the effects of natalizumab treatment interruption.

“Some studies suggest that withdrawal of natalizumab treatment for >3 months may be associated with return of MS disease activity,” wrote Robert J. Fox, M.D., of the Mellen Center for Multiple Sclerosis at the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio and colleagues. “Following natalizumab discontinuation, MS disease activity exceeded prenatalizumab disease activity in some studies but not in others. The timing of the return of disease activity and optimal monitoring and treatment strategies for patients discontinuing natalizumab are not known.”

The Randomized Evaluation of Sedation Titration for Respiratory Failure (RESTORE) was a randomized, partially placebo-controlled exploratory study examining MS disease activity during a 24-week interruption of natalizumab therapy. Inclusion criteria were having neither gadolinium-enhancing brain lesions on screening MRI nor relapses during the prior year while taking natalizumab. In a 1:1:2 ratio, participants (n = 175) continued natalizumab (n = 45), switched to placebo (n = 42), or received other immunomodulatory therapy (n = 88), such as IM interferon β-1a (IM IFN-β-1a; n = 17), glatiramer acetate (GA; n = 17), or methylprednisolone (MP; n = 54), for 24 weeks. Every 4 weeks, participants underwent clinical and MRI evaluations.

Relapse and MRI activity

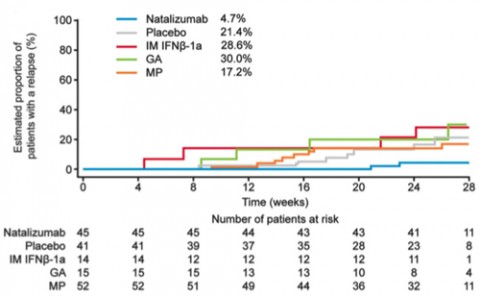

Beginning at 12 weeks (in three patients), MRI disease activity recurred in 49 (29%) of 167 patients evaluable for efficacy. These included none of 45 (0%) on natalizumab, 19 of 41 (46%) on placebo, 1 of 14 (7%) on IM IFN-β-1a, 8 of 15 (53%) on GA, and 21 of 52 (40%) on MP.

Relapses occurred in only 4% of natalizumab patients, compared with 15% to 29% of patients receiving placebo or other treatments. These occurred as early as 4 to 8 weeks after the last natalizumab dose (in two patients). Because of disease activity, 50 of 167 patients (30%), all receiving placebo or other treatment, restarted natalizumab early.

Most patients who developed defined MRI disease activity restarted natalizumab during the randomized treatment period even though they were clinically asymptomatic, suggesting that physicians made clinical decisions based on MRI findings.

“MRI and clinical disease activity recurred in some patients during natalizumab interruption, despite use of other therapies,” the study authors wrote. “This study provides Class II evidence that for patients with MS taking natalizumab who are relapse-free for 1 year, stopping natalizumab increases the risk of MS relapse or MRI disease activity as compared with continuing natalizumab.”

Study limitations include inadequate design and power to compare the efficacy of the different alternative immunomodulatory therapies, including lack of randomization to these therapies.

“Results from RESTORE and other studies suggest that, in patients who discontinue natalizumab, brain MRI surveillance beginning 12–16 weeks after the last natalizumab infusion may be useful for identifying patients with a return of disease activity,” the study authors concluded. “The results suggest planned dosage interruption is likely not useful for the management of most patients switching to no treatment or to the disease-modifying therapies employed in this study. The extent and time course of disease recurrence described in this randomized prospective study are highly relevant for all patients discontinuing natalizumab treatment for any reason and—together with the recognition of risk factors for PML—may also inform decisions about the timing and choice of alternative therapies.”

Key open questions

- How might greater use of brain MRI surveillance after stopping natalizumab help to identify otherwise asymptomatic patients in whom disease activity is returning?

- How might use of other specific immunomodulatory therapies lower the risk for relapse during natalizumab interruption?

Disclosures and sources of funding

Biogen Idec Inc. (manufacturer of natalizumab) sponsored this study and employed three of the study authors. Some of the other study authors reported various financial disclosures involving Allozyne, Avanir, Biogen Idec, EMD Serono, Novartis, Questcor, Teva, Xenoport, AbbVie, Genzyme, Sanofi-Aventis, Bayer Schering, LFB, Merck Serono, Bayer HealthCare, Therapeutic Advances in Neurological Disorders, BioMS, Acorda, Berlex, GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer, Actelion, BaroFold, Bayhill, Boehringer Ingelheim, Elan, Genmab, Glenmark, MediciNova, Santhera, Shire, Roche, UCB, Wyeth, Swiss MS Society, Swiss National Research Foundation, European Union, Gianni Rubatto Foundation, the Novartis and Roche Research Foundations, Department of Defense, Almirall, Genentech, and/or Infusion Communications.

Comments

Let me begin by disclosing that I have received consultant honoraria from Biogen Idec and Royalty Pharma, speaker honoraria from Genzyme and Teva, and travel expense reimbursement by Merck Serono.

This study conducted by Fox and colleagues is the first prospective randomized placebo-controlled trial to address the effects of natalizumab interruption by assessing clinical and MRI outcomes. The study largely confirms findings from several retrospective and small uncontrolled prospective studies, which have assessed recurrence of disease activity after cessation of natalizumab treatment, but it also increases our knowledge on the timing of disease recurrence and the possible effects of switching to other treatments.

The study enrolled 175 relapsing-remitting MS patients who had been without relapses and MRI disease activity the previous year and assigned them to either continued natalizumab treatment (n = 45), placebo infusions (n = 41), or open-label treatment with either interferon β1-a (n = 14), glatiramer acetate (n = 15), or methylprednisolone (n = 52) for a 24-week period.

The findings provide evidence (Class II) that natalizumab interruption is associated with recurrence of disease activity; 46% of the placebo-treated patients had MRI disease recurrence compared to none of the patients on continued natalizumab, while 17% of the placebo-treated patients had relapse compared to 4% of the patients on continued natalizumab. MRI disease activity appeared from week 12, while relapses were observed from week 8 and the peak of disease recurrence around week 20.

As the authors correctly emphasize, an important limitation of the study is that the trial was not designed to compare the efficacy of the different alternative therapies on recurrent disease activity. Although data on DMT are presented for each therapy, the open-label design, small size of the groups and the marked variance in relation to baseline EDSS, and frequency of high and low disease activity make comparisons between the DMT subgroups potentially misleading. However, the findings indicate that shifting to first-line therapies like interferon β, glatiramer acetate, or methylprednisolone is invariably associated with recurrence of MRI disease activity to the same level (37%) as placebo-treatment (46%), which is also reflected by a comparable relapse rate for DMT and placebo (19% and 17%).

The clinical implications of the study are several. The study makes clear that within 24 weeks of natalizumab cessation, about half the patients have recurrent disease activity, and this highlights the need for improving the treatment-shift strategies. Indeed, the data on when recurrent disease activity can be expected may help to encourage a shorter washout interval when shifting from natalizumab to fingolimod, along with the emerging data from different natalizumab-to-fingolimod studies. Finally, the findings indicate that shift to first-line therapies or methylprednisolone seems ineffective and thus appears to be a bad choice for the patient about to stop natalizumab.

Future research should proceed in several areas. We need to know more about whether and how latent JC-virus disseminates into the brain and what role natalizumab plays in the development of PML. Secondly, biomarker studies may be of use. One study indicates the possible usefulness of L-selectin, which may help refine the identification of natalizumab-treated patients at risk of PML, while another study on cell-bound natalizumab may be useful in identifying patients at risk of recurrent disease activity during washout periods. Finally, the still more complex landscape of RRMS treatments demands development of new treatment-shift strategies, both for shift to fingolimod and for shift to new and emerging drugs.