MS Family Planning 101: Should DMTs Be Discontinued Before and During Pregnancy?

The recent availability of a variety of disease-modifying therapies for RRMS raises many questions about when and which DMTs patients should start or stop before and during pregnancy

Like many autoimmune diseases, multiple sclerosis (MS) affects twice as many women as men. The average patient will be diagnosed at age 30, right around the time when many are starting or growing their families. Pregnancy is not a risk to women with MS, and the rate of relapse during pregnancy actually tends to decrease. But the relapse rate goes up in the first 3 months after birth (Confavreux et al., 1998). While many disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) are available for patients diagnosed with relapsing forms of MS, all can pose a risk to the fetus, and none are indicated for use during pregnancy.

Stopping DMTs to get pregnant

In an interview with MSDF, Bonnie W., a mom with relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS), expressed a fear common to many in her position: fear of disease progression while off therapy and the risk of permanent damage while trying to become pregnant. “[My husband and I] decided that we were ready for another baby, and then I had to stop [teriflunomide (Aubagio, Sanofi)],” she said. “I took a medicine to clear my system of the drug. And, so it's been about 4 months and we're still not pregnant. I'm not going to keep trying [to conceive] forever, because I want to get back on my meds.”

Indeed, the advice is for patients to stop taking all currently available DMTs for 1 or more months before becoming pregnant. Even though patients such as Bonnie know that none of the DMTs are 100% effective or curative, the drugs do reduce the risk of relapse and some other measures of disease progression. While patients and clinicians want to avoid causing damage to the fetus, this leaves patients trying to have a baby at risk for new relapses, at least until the poorly understood protective effects of pregnancy go into effect.

Elizabeth Crabtree-Hartman, M.D., sees about 1000 MS patients in her role as an associate clinical professor of neurology and the director of patient education and support at the UCSF Multiple Sclerosis Center. In an interview with MSDF she said, “Something that's really important to keep in mind—and this is a good tip for community physicians—if a person is on DMT and thinking about pregnancy, if that person is taking oral contraceptives, it's really important to discontinue the use of oral contraceptive pills and use a different means of birth control, while the person is on DMT, to establish a regular cycle while the person's MS is still covered by the DMT, prior to doing a washout for pregnancy. Because the idea is that we want the person to be uncovered for as little time as possible.”

DMTs and FDA pregnancy categories

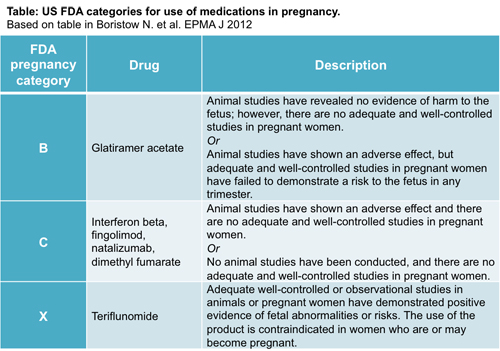

But what is the evidence that any overlap between DMT use and pregnancy affects birth outcomes? The most widely used information available is the classification given by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) based on the drug’s potential to cause birth defects, which relies on data provided by the pharmaceutical company before a drug can be approved. The drugs are given a category of A, B, C, D, or X.

Only one DMT, teriflunomide, is classified in pregnancy category X. In this case, animal or human studies have demonstrated fetal abnormalities, and the risk of use in pregnant women outweighs the benefits. However, this is not the case for other DMTs. Crabtree-Hartman explained, “With all of the agents, the preference is that pregnancy or conception occurs when the patient is off of medication. Glatiramer acetate (GA) is an exception.”

That is because GA (Copaxone, Teva) is classified as pregnancy category B, the safest among DMTs. Per definition, animal studies have not demonstrated a risk to the fetus, but no well-controlled human studies have been done. All other current DMTs are category C, in which animal studies have shown adverse effects on the fetus, there are no well-controlled studies in humans, but potential benefits may warrant the use of the drugs. In these cases, the neurologist needs to assess whether the use for the patient is worth the potential risk to the fetus.

Obtaining enough data in humans is difficult, given the ethical considerations of doing testing in pregnant women. Rather, pharmaceutical companies are required to set up pregnancy registries, in which patients can report accidental pregnancies while taking DMTs. This way, pharmaceutical companies can track their pregnancy and birth outcomes. Understandably, it can take many years to enroll enough patients in these registries. Many of the DMTs haven’t been around long enough to accumulate more than a few years of data that would indicate the long-term effects of DMT exposure to babies during conception or in utero.

For DMTs that have been on the market the longest, such as the aforementioned GA or the various interferon β options (currently four different ones are available: Avonex, Biogen; Rebif, Serono/Pfizer; Betaseron, Bayer; Extavia, Novartis), more data about outcomes are available.

A 2013 review by Bruce Cree, M.D., provides an excellent summary of what’s known (Cree, 2013). Since then, Bayer also published its pregnancy registry data (Coyle et al., 2014) for Betaseron. In brief, neither GA nor the various interferon β formulations show evidence of causing infertility or teratogenicity. However, there are some indications that the interferon β’s may result in lower mean birth weight.

For newer DMTs, on the other hand, the available data come mainly from animal studies, leaving patients and doctors to interpret these findings while balancing the risks and benefits of continuing treatment while the patient is trying to conceive.

Leaving the choice to neurologists and patients

It has been suggested (Langer-Gould, 2014) that the approval of fingolimod (Gilenya, Novartis) prompted more serious conversations about DMT use during pregnancy in MS patients. Fingolimod was the first small-molecule oral drug for MS and, as such, is more easily transported across the placenta. It is also classified as pregnancy category C, but the potential for teratogenicity appears to be higher than for the interferon β’s.

Novartis recently released data from patients who had become pregnant while on fingolimod during their clinical trial (Karlsson et al., 2014). The study only included 66 pregnancies with exposure to fingolimod and, while some negative outcomes were reported, the results were not conclusive due to the small size of the study.

In an interview with MSDF, Danny Bar-Zohar, M.D., the global program head for Gilenya at Novartis, commented on this report: “To derive conclusions from two years of clinical studies in a couple of hundreds of patients into the … bigger population is something that needs to be done very cautiously.” However, he also remarked that “if we read the … label, it's not that it's totally forbidden; you can take Gilenya during pregnancy if it is considered that the benefit will outweigh the risks.”

Bar-Zohar made it very clear that Gilenya’s label indicates that women of childbearing potential that wish to get pregnant should stop treatment with fingolimod.

Ultimately, neurologists’ input is crucial to determine whether a particular patient should remain on a DMT during conception and pregnancy.

Navigating treatment options

Given the same patient, different neurologists may suggest different treatment avenues. This is not surprising, since there are no set guidelines in place, aside from the label indications, to guide clinicians in the selection of DMTs for any MS patient, let alone for patients who wish to become pregnant.

On the idea of generating an algorithm to help select a DMT, Crabtree-Hartman remarked, “It is so difficult to do, because the variables leading into decisionmaking are not just based on our opinion or our clinical experience or even published literature from large data sets. The patient's perspective, tolerability and safety, and route of administration have to be factored in. There's no one right answer. The patient has to be—I feel very strongly—the patient has to be involved in the decisionmaking process.”

She encourages patients to visit an MS specialty center in addition to their community neurologist. MS specialty centers have the luxury of time to meet with patients and also can provide high-quality, data-driven updates on treatment options, which are many and quickly changing.

Predictors of postpartum relapse

The current recommendation in the United States is for all MS patients to start DMT treatment as soon as possible. This raises the question: If a patient is planning to start a family in the very near future, should she even start a DMT in the first place, especially if stopping it could cause rebound disease later? For patients with high disease activity, the consensus appears to be that it’s crucial for MS patients to get their disease under control before becoming pregnant.

Crabtree-Hartman said, “Because frequent relapses going into pregnancy is a predictor for postpartum relapse, to me, it's important for a person's MS to be under control for close to a year prior to entering pregnancy.” Other risk factors for postpartum relapses are relapses during pregnancy and the level of disability upon entry to pregnancy, where a high level of disability has an increased risk of relapse postpartum.

This falls in line with a recent study that evaluated 893 pregnancies in 674 women with MS and found that DMT exposure before pregnancy and low relapse rate were protective against postpartum relapse (Hughes et al., 2014). In accordance with this, Crabtree-Hartman said, ”I would recommend that we start at a higher efficacy agent if a person presents with aggressive MS, and you might have to delay family planning for a year or so.” Natalizumab (Tysabri, Biogen Idec) is one of these high-efficacy DMTs.

Natalizumab, approved in 2004, is a monoclonal antibody that is given as an infusion. As a pregnancy category C DMT, its use in pregnant women is not recommended, since it can cross the placenta after the first trimester. But stopping treatment with natalizumab puts patients at an increased risk of relapse (Fox et al., 2014; also discussed in an MSDF article).

Whether natalizumab causes rebound in the first place has been contested (Fox and Kappos, 2008) and is still up for debate. A recent study with 32 patients estimated the cumulative probability of rebound at 39%, with severe relapses in 9% of patients (Gueguen et al., 2014). But a study of 124 patients who had taken 24 doses of natalizumab observed no rebound activity (Clerico et al., 2014), suggesting that longer treatment with natalizumab may decrease the risk of rebound.

Depending on how many doses of this DMT a woman has received before becoming pregnant, it might be advisable to introduce natalizumab earlier—possibly even in the third trimester—to try to provide as much continuous coverage with DMT as would be safe for the fetus, while trying to prevent a postpartum rebound.

But there are only 14 reported cases of women taking natalizumab while pregnant. A series of case studies published by European researchers first reported exposure to natalizumab in pregnancy (Bayas et al., 2011; Fagius and Berman, 2014), which then led to a more controlled study of 12 women with highly active MS who were treated with natalizumab during the third trimester (Haghikia et al., 2014). The latter study suggests that this use of natalizumab could be indicated as a way to reduce postpartum relapses. The investigators do suggest having a pediatrician involved as part of the patient’s medical team, since the use of this DMT during the third trimester can cause hematologic alterations in the newborn baby.

One group goes further than most to advocate the use of other DMTs during the first weeks of pregnancy in patients with low disease activity, although these investigators acknowledge that more studies are needed before making a definitive suggestion. They collected data from over 100 women, 61 of whom had taken GA, IFN, or corticosteroids for at least the first 8 weeks of pregnancy.

They showed that mothers who received no DMT during pregnancy had significantly increased EDSS scores compared to mothers who had received either DMT during pregnancy. They saw no difference with corticosteroids. The relapse rate postdelivery was also significantly decreased in women with DMT exposure (p = 0.004). However, the mean EDSS score at the start of pregnancy in the group of women taking DMT during pregnancy was higher than in those who did not take DMT (p = 0.02), which might confound the results. The authors speculated that this is due to the fact that the group of patients who did not remain on DMTs when trying to conceive or while pregnant left themselves unprotected during that time, causing progression in disability, which was reflected in the higher EDSS scores measured after delivery. But there is not enough data to show a causal relationship between the two (Fragoso et al., 2013).

Yara Dadalti Fragoso, M.D., Ph.D., a neurology professor at the Universidade Metropolitana de Santos in São Paulo, Brazil, and the first author of this study, said in an email correspondence with MSDF: “I believe patients should not stop treatment for MS while trying to become pregnant. MS is a serious disease that cannot be treated one day and not treated the next day. There are options for treatment that are deemed adequate for a woman trying to conceive. As for pregnant women taking drugs for MS, my advice is based upon disease activity. It is not rare that I recommend a woman should continue her treatment throughout pregnancy.”

Other DMTs to consider during pregnancy

The discussion of DMT use during pregnancy raises the question of whether dimethyl fumarate (Tecfidera, Biogen) may also be considered. This oral medication is very effective in patients with high disease activity, but it is the newest DMT approved for RRMS. The risk of rebound disease activity is unknown, so it’s unclear whether clinicians would be compelled to use it during pregnancy as with natalizumab. Animal studies have shown different toxicity levels depending on the species used (also reviewed in Cree, 2013).

The lack of data showing whether rebound activity occurs after use of dimethyl fumarate or other DMTs aside from natalizumab supports the decision not to take these DMTs during pregnancy. By analogy, the DMT most likely to cause rebound would be fingolimod, since it also stops immune cells from reaching the brain (like natalizumab, although via different mechanisms). There is only one case report of a patient experiencing rebound after taking fingolimod (Havla et al., 2012). Other reports of rebound after fingolimod use are from patients who had previously taken natalizumab, which introduces a confounding variable (Sempere et al., 2013, and Hoepner et al., 2014). Bar-Zohar was adamant in stating that there is no evidence of rebound following stopping fingolimod treatment.

Getting the body ready for making a baby

In most cases, the risk of harming the fetus is judged to be greater than the benefit of reducing disease progression for the patient. But not all pregnancies are planned. Therefore, a better understanding of the effect of DMTs on fetal development would also be useful for patients with unplanned pregnancies.

It’s not just women with MS that need to think about whether their use of DMTs could affect their offspring. Since teriflunomide can be detected in human semen, its use is also contraindicated for male patients who are trying to conceive. However, the available data suggests that other DMTs are less problematic for men wishing to conceive.

Canadian researchers were the first to show that birth outcomes in fathers with MS did not differ from those without MS (Lu et al., February 2014), irrespective of DMT use, something that has been shown for women previously (Finkelsztejn et al., 2011). “When we talk to the community,” shared Ellen Lu, Ph.D., a postdoctoral associate at the University of British Columbia, “with people that have MS, … one of the things that people [ask] us [is] ‘Well, what about the men? You know, we contribute like 50% of the genes as well.’ ” She and an Italian group also evaluated the effect of GA and interferon-β use in fathers during conception (Lu et al., May 2014 and Pecori et al., 2014) and found no evidence of exposure being associated with lower birth weight or gestational age, or higher spontaneous abortion or cesarean rates.

Crabtree-Hartman emphasized that “it’s very important to counsel patients with agents with a pregnancy category X that even an unplanned pregnancy would prompt potentially very difficult decisions. So counseling comes up with our male patients, particularly since teriflunomide was FDA-approved.“

Not only is teriflunomide a category X DMT, but it can also stay in the body for up to 2 years. In this case in particular, but also for all other DMTs, the washout period is important to consider as part of planning for pregnancy. For most other DMTs, experts suggest stopping treatment 3 to 12 months before trying to conceive. This is not clearly indicated in the product labels for GA, interferon β, or dimethyl fumarate, although patients report stopping a few weeks to 3 months before trying to conceive. For teriflunomide, cholestyramine can be taken to eliminate the drug more quickly from the body, a process that takes a few weeks until the levels of the DMT drop under 0.02 mg/l; its use is recommended for both women and men.

While there are many unanswered questions that neurologists and patients have to contend with about DMT use during pregnancy, for Bonnie W. those worries are over. A month after MSDF first spoke with her, she gave us the happy news that she is now pregnant. Bonnie W. had taken cholestyramine and had stopped taking teriflunomide a few months before she got pregnant, so she knows that the DMT she was taking will not affect her baby, and she no longer has to worry about the risks of staying off DMTs while trying to conceive. While a lot of data summarized here might predict an increase in the risk of postpartum relapse, for this one specific person it’s hard to say for certain what will happen after delivery. Now Bonnie W. and her neurologist will have to consider when she should start taking DMTs again postpartum, because there’s the question of whether DMTs are safe during lactation. That question will be one of the subjects of the next article in this series on pregnancy and childbirth in people with MS.

Key open questions

- What is the impact of starting DMTs and then stopping them while trying to conceive?

- How does this affect the patient physically and psychologically?

- What are the optimal guidelines for neurologists to follow when advising patients about which DMT to take if they wish to become pregnant in the future?

- What is the threshold at which the benefits of DMT use during pregnancy outweigh the risk? How does this vary by DMT?

- What’s the best design for animal or human studies to determine the effect on birth outcomes of use of DMTs during conception and pregnancy?

Disclosures and sources of funding

Bonnie W. reports no disclosures.

Danny Bar-Zohar, M.D., is an employee of Novartis.

Elizabeth Crabtree-Hartman, M.D., reports having served on the advisory panels for Biogen and Novartis.

Ellen Lu, Ph.D., disclosed that she “was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (Canada Graduate Scholarships: Master’s and Doctoral Research Awards), the Multiple Sclerosis Society of Canada (MSc and PhD Research Studentships) and the University of British Columbia (Graduate Entrance Scholarship, Faculty of Medicine Graduate Awards and Four Year Doctoral Fellowship). She has received travel grants from the University of British Columbia, Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute, European Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis, European Neurological Society and the endMS Research and Training Network/Multiple Sclerosis Society of Canada to present at conferences.”

Yara Dadalti Fragoso, M.D., Ph.D., reports no disclosures.

Image credit

Thumbnail image on landing page by Sean Dreilinger.