MS Patient, Ph.D.: PPMS: A New Hope?

A blog post at a site run by UK MS researchers begins in a way that brings hope to the progressive MS crowd because, well, at least it actually mentions PPMS:

A blog post at a site run by UK MS researchers begins in a way that brings hope to the progressive MS crowd because, well, at least it actually mentions PPMS:

“… the progressive phase of MS is present from the beginning of the disease. How do we know this? Studies of MSers presenting with their first clinical attack already have significant brain atrophy on MRI and about 30-40% have subtle cognitive impairment. When you look even earlier in people diagnosed with asymptomatic MS, or RIS (radiologically isolated syndrome), you find brain atrophy is present in about 25% of these subjects. In other words the progressive phase of the disease can be present before the disease manifests. The only reason MSers don’t have progressive physical disability from the outset is that their brains and spinal cords adapt to damage by using up their reserve capacity. It is only once this reserve capacity is exhausted that progressive MS manifests itself as secondary progressive MS. We think MSers with PPMS have the same problem, the only difference is they were unlucky not to have relapses. Relapses at least allow us to get in with DMTs early to slow, or prevent, further damage. Therefore it makes little sense to wait until progressive disease starts to target progressive MS. We need to start neuroprotective drugs as soon as possible in the course of the disease.”

So, not that promising, actually. The mention of PPMS ultimately rules PPMSers out because, as the authors suggest, if you don’t show symptoms until you’re progressive, no one knows you have MS. It’s not as though everyone gets an annual brain scan to monitor for atrophy as a marker of overall health, like a cholesterol test. Indeed, one of the current criteria for a PPMS diagnosis is that symptoms persist for at least a year, and most folks with PPMS receive an official diagnosis after a much longer period. Thus, it’s unlikely that awareness of this invisible process during a potentially open window for therapy will change anything in the near future. Meanwhile, PPMSers walk through life in ignorance that their reserves are fizzing away until the day when walking starts to become difficult. Then, it’s too late.

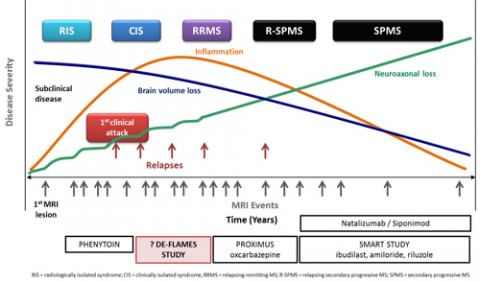

Further into the quoted post is a discussion of upcoming trials that hold promise for people with progressive MS. But a closer look shows that these trials are still for people with RRMS that progresses to SPMS, not for those with PPMS. Again, without those “lucky” relapses before progressive disease manifests, who’s to know who the future PPMSers are so that interventions can help before progression? In a graph in the post that traces the studies and MS trajectories, PPMS doesn’t even make an appearance.

And that brings up two questions for people with PPMS. First, at least according to these authors, PPMSers have the same problem as other patients with progressive MS: They burn up their reserves and have nothing left, so the result is progressive disease. My typical experience with neurologists is that they focus almost entirely on the question of relapse and white matter hyperintensities. Neuroradiologists seem to have the same predilection for bright things when it’s an MS workup.

If we’re talking brain atrophy, though, and loss of reserve, we’re talking about a different measure entirely from looking for bright spots. Atrophy happens to be a measure that can be apparent even at the first hints of clinically isolated syndrome, and research indicates that it might be an early process in PPMS. So why don’t more neuros consider atrophy when PPMS is suspected?

In spite of the likelihood of early brain atrophy in progressive MS, not once has my brain volume been assessed or cross-comparisons of volume made from reading to reading. In fact, in my experience, most neurologists give a glance at the imaging report and possibly an even briefer glance at the MRI images before moving on. Meanwhile, for people with progressive disease, at least according to the DE-FLAMES researchers, those years of waiting for an official diagnosis that then holds no hope for treatment could be time—and brain volume—wasted.

The second question relates to when PPMSers enter studies. For the limited reports that do involve PPMSers and find no effects, the intervention may well have come too late. Some groups have examined white matter lesion evolution longitudinally, not always in the context of DMT use. Yet findings indicate that “early and persistent” use of DMTs in the context of CIS delays disability progression. What would outcomes look like if atrophy measures were taken at presentation of CIS and patients treated with DMTs and followed for several years, including those who ultimately receive a PPMS diagnosis? That seems like a crucial study for better understanding—and possibly identifying and treating—PPMS.

As someone who’s been playing that diagnosis waiting game since 2008, the possibility that this delay might have proved irreversibly damaging makes my brain—or what might be left of it—hurt, figuratively speaking. It’s just further confirmation of what I find in every clinical visit and even in these trials targeting progressive MS that exclude PPMSers: When it comes to PPMS, everything clinicians and researchers think is a “rule” about MS doesn’t apply. I wish that for the sake of my brain (and spine, where most of my troubles lie) and for others with probable or confirmed PPMS diagnoses, clinician training and research trials would incorporate that fact.

Key open questions

- Why don’t more neurologists look at atrophy and gray matter loss in particular when PPMS is suspected?

- What would outcomes look like if atrophy measures were taken at presentation of CIS and patients treated with DMTs and followed for several years, including those who ultimately receive a PPMS diagnosis?

Read other MS Patient, Ph.D. blog posts.